March 15

March 15 is synonymous with betrayal, treachery, back-stabbing and front-stabbing. It’s the anniversary of the assassination of Julius Caesar by Brutus and the Roman Senate in 44 B.C.

But in Hungary, March 15 is synonymous with freedom and independence, so whip out your cockades and join the Hungarians as they sing their National Song today.

Turns out the Hungarians celebrate March 15, 1848, not 44 BC.

In 1848, as the fervor of revolution swept through Europe…

Nowhere else did the crowd assume such an emblematic character as in Hungary. The Chartists crowds of London might have been larger, the fighting on the barricades of Paris, Prague, Vienna and Dresden more intense, but Budapest instigated the only total revolution in 1848-1849, and Hungary’s crowds were the last holdouts.

Alice Freifeld, Crowd Politics in the Hungarian Revolution

March 15 marked the day that news reached rebellious students and intellectuals in Budapest that revolution had broken out in Vienna, the center of the Hapsburg’s empire. The rebel movement’s leaders had planned a protest march to take place on March 19, but when news hit Budapest, they spontaneously decided to demonstrate in celebration.

And it’s a good thing. The government had gotten wind of the demonstration, and had planned to arrest the movement’s leaders on March 18.

Students marched from Pest to Buda—the two cities that make up the aptly named Budapest—to protest the Hapsburg-dominated monarchy in Austria. Along the way, massive crowds joined the demonstration, spurred on by news from Vienna and the songs of a 25 year-old poet named Sandor Petofi.

Petofi had been chosen to put the movement’s demands to paper. Deemed the “Twelve Points,” they were:

1. Freedom of the press, the abolition of censorship.

2. A responsible Ministry in Buda and Pest.

3. An annual parliamentary session in Pest.

4. Civil and religious equality before the law.

5. A National Guard.

6. A joint sharing of tax burdens.

7. The cessation of socage.

8. Juries and representation on an equal basis.

9. A national bank

10. The army to swear to support the constitution, our soldiers not be dispatched abroad, and foreign soldiers removed from our soil.

11.The freeing of political prisoners.

12. Reunion with Transylvania.

On the steps of the National Library Petofi led the crowds in the singing of his famous poem “Nemzeti Dal”, which to this day symbolizes Hungarian self-determination and freedom:

Rise up, Magyar, the country calls!

It’s ‘now or never’ what fate befalls…

Shall we live as slaves or free men?

That’s the question – choose your `Amen’!

God of Hungarians,

we swear unto Thee,

We swear unto Thee – that slaves we shall

no longer be!

from “Nemzeti Dal” (National Song)

Unprepared for the rebellions of March 13 in Vienna and March 15 in Budapest, the court was forced to acquiesce to the demands of the Hungarian National Assembly. Hungary became the first (and only) country during the revolutions of 1848 to undergo a peaceful transition.

+ + +

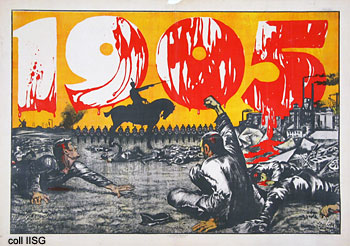

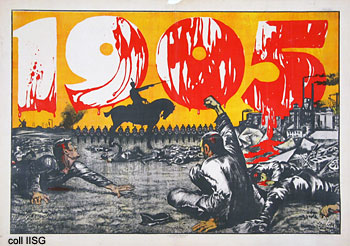

Peace was temporary phenomenon. Later that year the Austrian empire recovered from the shock and set about to reconquer Hungary. With the Russian Czar’s help, the Hungarian army was decimated. The Austrian army executed 14 Hungarian leaders, including the new Prime Minister.

Petofi is believed to have been killed at the Battle of Segesvar in Transylvania on July 31, 1849. He was 26 years old. By that time, the soldier-writer-revolutionary had written 10 volumes of Hungarian poems.

Throughout the past century and a half, March 15 has remained a symbol of the Hungarian struggle for liberty and self-determination.