February 8

When all the nations stand before the judgment seat and are asked to explain how they used their basic talents…the small Slovenian nation will dare without fear to present a thin book with title Prešeren’s Poems alongside the others.

— Josip Stritar

Don’t mess with the Slovenes when it comes to their national poet, France Prešeren. He gets, not one, but two days in his honor on the Slovenian calendar. Today, the anniversary of his death in 1849, is a national holiday known as Culture Day; many Slovenes celebrate his birthday as well.

France Prešeren was the son of a farmer, studied law, and spent most of his life as a lawyer and civil servant. He “led no revolutions, proposed no political programs, and died of tuberculosis, impoverished and almost alone, at the age of 49.”

Yet his popularity is unrivaled. Why? It wasn’t simply because his poems came to symbolize the Slovenes and their culture. According to many, Preseren’s poetry helped to save Slovenian culture:

“To understand Preseren’s importance we must appreciate that tiny Slovenia had no history of national statehood and no possibility of achieving political independence in the mid-nineteenth century. Simultaneously, there was a real chance that the Slovenian language would disappear…Through his creation—in response to the dual threat of Germanization or Croato-Serbinization—of a body of world-class poetry in his native language, Prešeren is seen to have ensured the very existence of the Slovenian nation.”

—Andrew Baruch Wachtel, Remaining Relevant After Communism: The Role of the Writer in Eastern Europe

His poetry mirrored the fortitude and resistance of the Slovenes, it represented a new form of literature and national identity for a group that had never coalesced as such. Appreciation of Preseren continued to grow through the 20th century, despite—or perhaps because of—the Yugoslavian regime of Tito, who sought to repress symbols of regional patriotism.

In the early 1990s Slovenes chose Preseren’s poem Zdravlijica (A Toast) as the young country’s national anthem:

God’s blessings on all nations

Who long and work for that bright day

When o’er earth’s habitations

No war, no strife shall hold its sway;

Who long to see

That all men free,

No more shall foes, but neighbors be…–from “A Toast”

Unlike “A Toast,” most of Preseren’s works convey a bleak pessimism that followed the poet all his life.

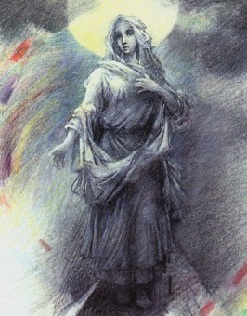

The piece that put Slovenian literature on the map, and ensured Preseren’s immortality,was Preseren’s only epic poem Krst pri Savici (The Baptism by the Savica) about the clash in Slovenia between the pagans and early Christian converts.

Excerpt from The Baptism by the Savica translated by Alasdair Mackinnon read by Katrin Cartlidge

| …The clash of arms has ceased throughout the land, Yet in your breast the storms of war still roll.

|

|