October 10

Double Tenth (10/10) celebrates the anniversary of the Wuchang Uprising which brought down a centuries-old dynasty in 1911.

Dozens of uprisings against the Qing Dynasty had failed between 1895 to 1911, most the work of small secret societies. What separated the Wuchang Uprising was that it originated from inside the Empire’s “New Army.”

The New Army had been created by the Emperor and his Manchu cabinet with the intention of putting down the many rebellions across China and protecting the country from foreign powers after the Boxer Rebellion.

The Army’s 8th Division, stationed in Hubei differed from other divisions throughout the country for several reasons:

First, the 8th Division was perhaps the most highly organized and cohesive.

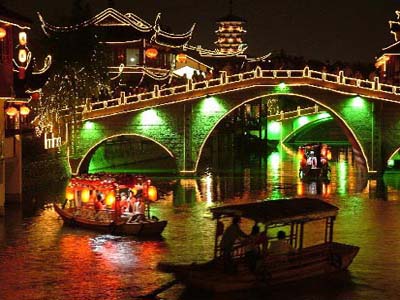

Second, it was stationed in a port city and major transportation hub, Wuhan, on the Yangtze. Wuhan had been a cosmopolitan port. Thus, its members had access to foreign ideas and influence.

Third, its officers were highly literate. Many had studied abroad or graduated from military university.

Many in the New Army’s 8th Division were also members of secret societies, the two biggest being the Literary Society and the Society for Common Advancement. The two underground organizations merged in September 1911, united by their opposition to the Manchu government. (Most of the Hubei army and the members of the secret societies were Han Chinese, who considered the Manchu as foreign as if they’d been European.)

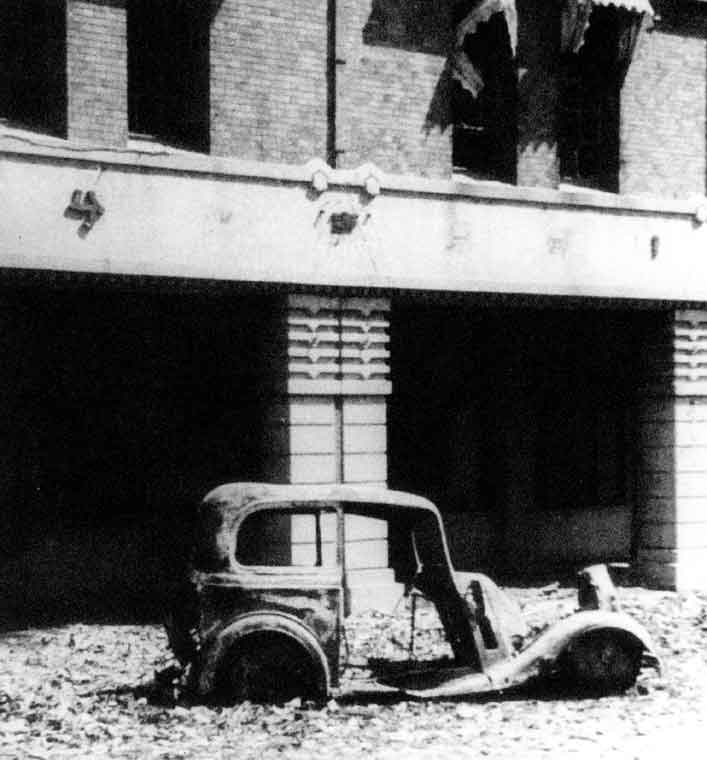

Ultimately, the military that was supposed to strengthen the Empire against foreign powers and subversive ideas was the cause of its downfall. On October 10, two-thousand New Army troops revolted. The governor fled Hubei, and within two days the Division occupied Hanyang and Hankou. As word of the rebellion spread, other provinces followed suit. By January 1, 1912, the revolutionaries had declared the new Republic of China, and the nearly three-century-old Qing Dynasty was no more.

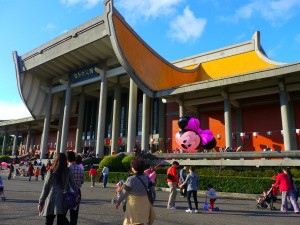

Future President Sun Yat-Sen has often been called instrumental in the Wuchang rebellion, but he was in fact in the United States at the time, garnering support for the cause. The story is he was somewhere between Denver and Missouri and learned about the revolution from a newspaper in the hotel. He spent the next two months convincing the Western Powers not to support the Qing government, and he returned to China on December 29, 1911.

Double Tenth is the national holiday of Taiwan, aka the Republic of China, although recently some Taiwanese have questioned why this is Taiwan’s national day, since Taiwan was not a part of China at the time of the rebellion and hadn’t been since 1895.

Chongyang is also known as Double Ninth. As the highest odd single number, 9 is considered especially lucky in Chinese culture. Chongyang falls on the 9th day of the 9th month of the Chinese calendar.

Chongyang is also known as Double Ninth. As the highest odd single number, 9 is considered especially lucky in Chinese culture. Chongyang falls on the 9th day of the 9th month of the Chinese calendar.

Confucius spent the next several years traveling through China, to the states of Wei, Song, Chen, Cai, and Chu.

Confucius spent the next several years traveling through China, to the states of Wei, Song, Chen, Cai, and Chu.

Okay, not what I had in mind.

Okay, not what I had in mind.