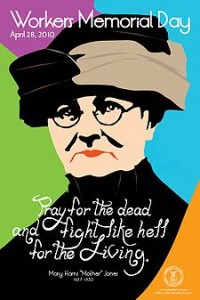

Last Monday in March

Actual birthday: March 31

“Money is not going to organize the disadvantaged, the powerless, or the poor. We need other weapons. That’s why the War on Poverty is such a miserable failure. You put out a big pot of money and all you do is fight over it. Then you run out of money and you run out of troops.” – César Chavez

On March 31 (or the last Monday in March), Americans in Arizona, California, Colorado, Michigan, New Mexico, Texas, Utah and Wisconsin celebrate César Chavez Day. César Chavez is most famous for organizing the historic food boycotts of the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, and for improving the working conditions of agricultural laborers in the United States.

“Do not romanticize the poor…We are all people, human beings subject to the same temptations and faults as all others. Our poverty damages our dignity.” – César Chavez

Chavez was born outside Yuma, Arizona in 1927.

During the “Roaring Twenties” a booming economy had increased the demand for cheap labor; however the Great Depression brought this to a halt. In 1929 the U.S. government began a program of mass deportation of hundreds of thousands of people of Mexican ancestry. The program was called “repatriation”, even though over half of the deportees had been born in the U.S. (The Forgotten “Repatriation” of Persons of Mexican Ancestry and Lessons for the War on Terror, Kevin Johnson)

The Chavez family was not removed, but they lost their farm and grocery store in Arizona, causing them to move to California to become migrant farm workers. César attended approximately 30 schools during these transitory years. Having completed the eighth grade he dropped out to help support the family after his father was injured in an accident. In 1944 he joined the Navy and served for two years.

In 1948 the Chavez married and moved to San Jose, California, where he met Father Donald McDonnell. Chavez later said about McDonnell:

“He told me about social justice, and the Church’s stand on farm labor and reading from the encyclicals of Pope Leo XIII, in which he upheld labor unions. I would do anything to get the Father to tell more about labor history. I began going to the bracero camps with him to help with the mass, to the city jail with him to talk to the prisoners…”

Chavez was influenced by the works of St. Francis of Assisi and Gandhi. He joined Fred Ross’s Community Service Organization, initially organizing voter registration. After ten years he left the organization and moved his family to Delano, California to co-found what would become the United Farm Workers with Dolores Huertes. The prevailing belief at the time was that the migrant life of farm workers and high illiteracy rates made unionizing impossible.

However, by September 16, 1965 (Mexican Independence Day) Chavez had amassed over 1200 members who voted to join the grape strike organized by Filipino Americans in the AFL-CIO. The following year Chavez led strikers on a 340 mile march from Delano to the steps of the state capital building in Sacramento. In 1968 he held his first hunger strike to draw attention to the treatment of grape farm workers.

When Giumarra, the largest grape grower in California, was allowed by other grape growers to use their labels to minimize effectiveness of the boycott, the UFW extended the boycott to all California grapes

Over the next two decades, Chavez’s boycotts, strikes and fasts improved the working conditions of farm workers, increased wages, united Latino-Americans laborers, and reduced pesticide use. It was in pursuit of this last goal that Chavez kicked off the “Wrath of Grapes” campaign in 1986, and held his final hunger strike in 1988, lasting 36 days.

With respect to pesticides, Chavez compared the role of farm workers to that of the canary in a coal mine: sickness endured by the farm workers was the first sign of the harmful effects of pesticides that would later be evident in consumers.

Chavez died on April 23, 1993, in San Luis, Arizona. He had been in Yuma testifying in a civil suit filed by a lettuce grower suing farm workers for damages brought on by a UFW lettuce boycott in the 1980s. He died about twenty miles from his birthplace.

The following year, his wife accepted the Presidential Medal of Freedom in his honor.

“It is possible to become discouraged about the injustice we see everywhere. But God did not promise us that the world would be humane and just. He gives us the gift of life and allows us to choose the way we will use our limited time on earth. It is an awesome opportunity.” — César Chavez

“We want to be recognized, yes, but not with a glowing epitaph on our tombstone…” — César Chavez