October 14.

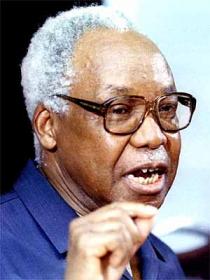

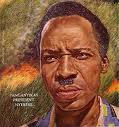

Julius Nyerere was born in 1922 just east of Lake Victoria in what was then Tanganyika. He herded sheep and “led a typical tribal life” in the village where his father was chief of a small tribe.

Julius Nyerere was born in 1922 just east of Lake Victoria in what was then Tanganyika. He herded sheep and “led a typical tribal life” in the village where his father was chief of a small tribe.

He began school at age 12 and studied to be a teacher at Makerere University in Uganda. After teaching for three years he received a scholarship to the University of Edinburgh.

He taught English, Swahili, and history in Dar es Salaam, and was elected head of the Tanganyika African Association, which he had helped to form as an undergraduate at Makerere.

Under his leadership TAA transformed into the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) a political force dedicated to Tanganyikan independence. As his reputation grew colonial leaders pressured him to choose between teaching and politics. Though he chose politics, his supporters would call him Mwalimu, or “teacher,” for the rest of his life.

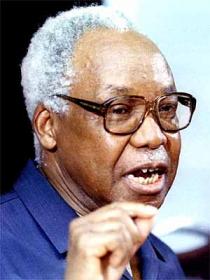

Nyerere traveled to New York to speak to the United Nations on Tanganyikan independence on behalf of the TANU, which became the most powerful political coalition in the country. In the late 1950s, Tanganyika won independence and Nyerere was elected its first president.

As President, Nyerere helped unite Zanzibar and Tanganyika, forming Tanzania. He was controversial in the West for increasingly distancing himself and the country from European governments and leaning more toward Communist China. For instance, his transformed the age-old African concept of Ujamaa (Familyhood) into an economic policy, melding socialism with traditional tribal government.

“Nyerere reasoned that political independence would have to be followed by quick material development, which, in turn, rested heavily on Western aid. What Nyerere did not wish to import from the West was the individualistic, self-seeking, acquisitive character of its capitalism…”

An African Voice – Robert William July

A few years before his death he gave an interview to Charlayne Hunter-Gault:

CHG: You mentioned the one-party rule in your country where you were president for four terms during which time you promoted the principle of “Ujamaa,” socialism, and you have acknowledged that it was a miserable failure…

NYERERE: Where did you get the idea that I thought “Ujamaa” was a miserable failure?

CHG: Well, I read that you said socialism was a failure…

NYERERE: A bunch of countries were in economic shambles at the end of the 70s. They are not socialists…You have to take in the values of socialism which we were trying to build in Tanzania in any society.

CHG: And those values are what?

NYERERE: And those values are values of justice, a respect for human beings, a development which is people-centered, development where you care about people. You can say ‘leave the development of a country to something called the market,’ which has no heart at all since capitalism is completely ruthless. Who is going to help the poor? And the majority of the people in our countries are poor. Who is going to stand for them? Not the market. So I’m not regretting that I tried to build a country based on those principles…Whether you call them socialism or not…what gave capitalism a human face was the kind of values I was trying to sell in my country.

In a time when so many of his contemporaries clung to power until losing it by coup, Nyerere chose to step down in 1985.

He died of leukemia on October 14, 1999. Today, on the anniversary of his death, the people of Tanzania remember Nyerere, his extraordinary leadership, and the principles on which Tanzania was founded.