November 5.

Remember, remember, the fifth of November,

Gunpowder treason and plot.

I see no reason, why gunpowder treason

Should ever be forgot!

We think of terrorism as a modern phenomenon but 400 years ago, before the first permanent settlement in North America, English authorities uncovered a terrorist plot that came one spark from away from blowing London to bits.

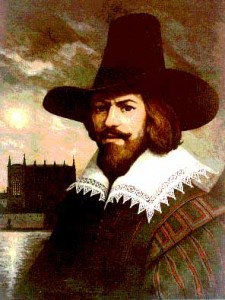

Guy “Guido” Fawkes was an Englishman who fought on the side of the Spanish Catholics in the Netherlands.

This would-be terrorist was described as “skillful in the wars”, “of excellent good natural parts, very resolute and universally learned,” “a man of great piety, of exemplary temperance, of mild and cheerful demeanour, an enemy of broils and disputes, a faithful friend, and remarkable for his punctual attendance upon religious observance.”

Not your typical mass-murderer.

Fawkes and his anti-English co-conspirators sought to destroy the entire British government in one foul swoop.

On November 5, 1605, after receiving an anonymous letter, authorities found Guy Fawkes and 36 barrels of gunpowder in the cellar of the House of Parliament. Fawkes was only one of several conspirators, but he was the one entrusted with the mission of setting off the explosion. Others had fled the country, expecting Fawkes would succeed.

So the popular rhyme goes:

Guy Fawkes, Guy Fawkes, t’was his intent

To blow up King and Parli’ment.

Three-score barrels of powder below

To prove old England’s overthrow;

By God’s providence he was catch’d

With a dark lantern and burning match.

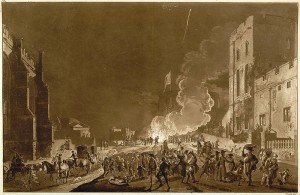

Ever since that day, youths in the United Kingdom set off firecrackers, light bonfires, and burn effigies of the notorious Guy Fawkes in memory of the miraculous discovery of the Gunpowder Plot of 1605.