May 13

Sightings of the Virgin Mary date all the way back to 40 AD when the Virgin Mary first appeared to the Apostle James in Spain. They’ve occurred all over the world, in communities big and small, and the sightings continue to this day. In fact…

“Just last week, the Virgin Mary appeared in the form of a stain on a griddle at Las Palmas restaurant in Calexico, California. More than 100 people have come to gaze upon it, manager Brenda Martinez told the Imperial Valley Press…” — The Standard – May 13, 2009

But the most famous sighting in modern times may be the one that took place on this day (May 13) in 1917 in Fátima, Portugal. As the World War raged throughout Europe, three Portuguese children—Francisco and Jacinta Marto, ages 9 and 7, and their cousin Lucia Dos Santos, age 10—were building a wall in the fields when their play was interrupted by a flash of lightning.

“They thought that a storm was brewing and herded the sheep together to take them home. They once again saw a flash of lightening and shortly afterwards they saw above a small holm oak tree a Lady dressed entirely in white and shining more brilliantly than the sun.”

http://www.marypages.eu/fatimaEng.htm

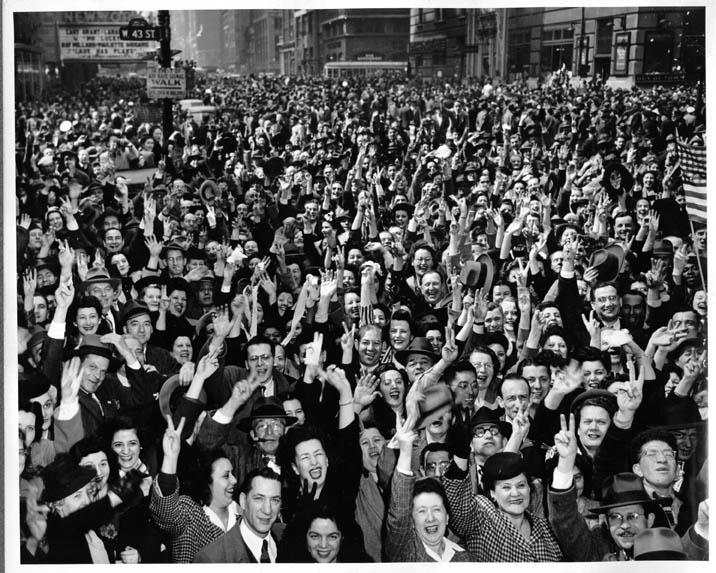

The apparition answered the children’s questions on heaven, and entreated them to return on the 13th of each month thereafter. At subsequent encounters she told them about heaven, hell, and God’s message. Over the next 5 months, word spread of the children’s encounters. By October 13, 70,000 people gathered in the field hoping to catch a glimpse of “Our Lady of Fátima” (now also known as “Our Lady of the Rosary”).

“After the long extensive rains, the sky became blue, people could easily look into the sun, which started to spin round like a wheel of fire which radiated wonderful shafts of light in all sorts of colours. The people, the hills, the trees and everything in Fatima seemed to radiate these marvellous colours.

Then the sun stood still for a moment then the wonderful thing that had happened reoccurred. It was repeated for a third time. But now the sun broke loose from the heavens and came down to earth with a zigzagging movement. It became bigger and bigger and looked as though it would fall on the people and flatten them. All were frightened and fell to the ground while they prayed for mercy and forgiveness.” — http://www.marypages.eu/fatimaEng.htm

Sadly, Francisco died only 2 years later and Jacinta the year after that. Pope John Paul II beatified Francisco and Jacinta on May 13, 2000. Lucia lived to the ripe old age of 97. She died in 2005.

May 13 is celebrated in Portugal and by many Portuguese Catholics in other parts of the world. On May 13, 2009, “The 13th Day”, about the miracle of Fátima, premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in France.