March 19

Las Fallas has been described as a “pyromaniac’s dream” and a cross between “a bawdy Disneyland, the Fourth of July and the end of the world.”

So how did the next-best-thing to the Apocalypse come to be celebrated on the feast day of Saint Joseph, adoptive father of Jesus?

Well, though St. Joseph’s Day is celebrated as Father’s Day across Italy, Spain, and Portugal, the Valencians chose to celebrate another calling of Joseph.

Joseph is also the patron saint of carpenters, an occupation that made up a good segment of the urban population in the Middle Ages. According to “Valencia en la epoca de los Corrogidores“, each Autumn, carpenters carved special planks of wood to serve as candle holders, either free-standing or hanging on the wall. Called estai, parot, or pelmodo, these medieval lamps provided light for carpenters to work by during the long winter nights.

Apparently the Valencian carpenters weren’t big fans of recycling. Each year on St. Joseph’s Day they would celebrate both their patron saint and the coming of spring by burning these special wooden candle holders along with any leftover wood.

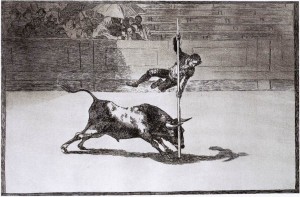

The pagan tradition of burning effigies on or near the spring equinox had long been a ritual in pre-Christian Europe. The Valencia carpenters had the idea of killing two birds with one stone. The dressed up the wooden lamps as unpopular local authorities—perhaps an unscrupulous sheriff or maniacal mayor—before burning them.

Over the centuries the pelmodos became more and more intricate. Today they are not candle holders at all, but are sculptures as big as houses, large float-like creations that portray anything from reviled politicians to hot-topic social issues, such as “globalization swallowing the world.”

After five days of festivals and celebration these miraculous, almost supernatural creations go up in smoke, just as in days of yore. Called “La Crema”, the bonfires take place on the evening of Saint Joseph’s Day, March 19, and for one long night the conflagration makes Valencia look like —well, let’s just say Nero’s Rome couldn’t hold a candle.

(the flames really get going around 50 seconds)

La Fiesta de Las Fallas (Spanish)