December 25

Behold! the angels said, ‘Oh Mary! God gives you glad tidings of a Word from Him. His name will be Christ Jesus, the son of Mary, held in honour in this world and the Hereafter, and in (the company of) those nearest to God.

— Qur’an 3:45

Today we celebrate Jesus Christ’s 2011th birthday.

Actually, no.

We don’t know the year Jesus was born. But it’s believed he was born at least four years prior to the year we count as 1 A.D. because King Herod the Great, whom Matthew cites as king when Jesus was born, died in 3 or 4 BC.

One theory for this discrepancy is that Dionysius Exiguus–the sixth century monk who created the A.D. dating system (short for Anno Domini Nostri Jesu Christi or “in the year of our Lord Jesus Christ”)–forgot to calculate the four-year reign of Emperor Octavian when adding up the years since the birth of Christ. Thus, the year he deduced to be 525 AD should have been 529.

Another theory states that Jesus was born even earlier, since the census that Luke mentions as the time of Jesus’s birth [This was the first census that took place while Quirinius was governor of Syria – Luke 2:2] occurred every fourteen years. Working backward, historians figured the first census would have been conducted in 8 BC.

So you see, we’re already in the future: 2019 AD.

But whether we’re wishing Jesus a happy 2011th, 2015th or 2019th birthday, we’re almost certainly celebrating the wrong day.

There’s no hint in the Gospels as to the day or even the season of Christ’s birth. A fact which has led some Christian denominations to exclaim that, had God wanted us to celebrate the birthday of the Lord, He would have given us some indication of the date.

In 4000 Years of Christmas, Episcopalian minister and scholar Earl Count recounts that the Romans celebrated December 25 as the birthday of the Sun God Mithra, a tradition inherited from Persian Mithraism. Similarly, the Annunciation of Christ, observed 9 months earlier on March 25, coincided with the Spring Equinox, which was celebrated as the New Year in the Near East.

In fact, Dionysius himself never considered the first day of the Christian era to be Christ’s birth—theoretically December 25, 1 AD—but Christ’s conception—aka, the Annunciation—on March 25.

That led to some confusion. As late as 18th century the English still marked March 25 as the start of the calendar year. (i.e., March 24, 1699 was followed by March 25, 1700. Yes, these are the people that cursed us with the Imperial measurement system of feet and pounds.)

In the United States, Christmas–a holiday once banned by the Puritans–has far outstripped the popularity of the Annunciation, or any holiday for that matter, partially due to its potential for consumerism in the 19th and 20th centuries. Which has led the folks at The Good News to ask, not how can we put the Christ back into Christmas, but “How can we put Jesus back into the season when He was never part of it to begin with?”

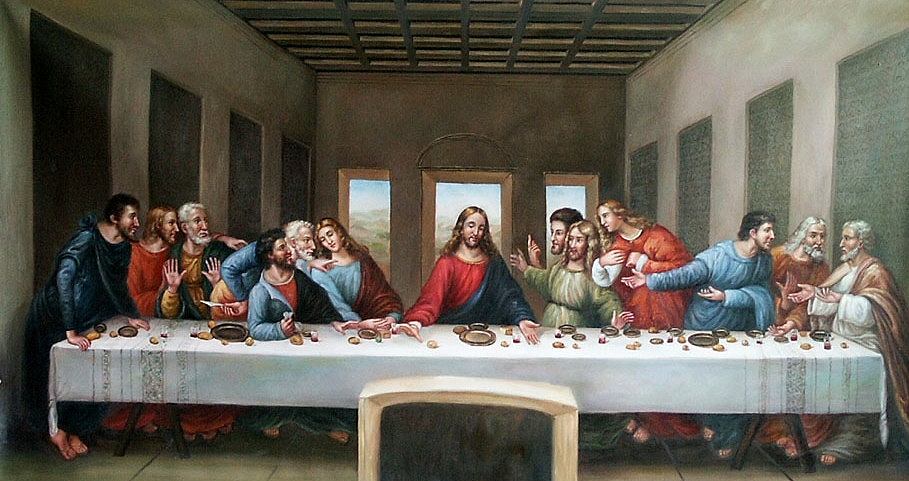

Well, regardless of how Christmas was created, it has become the de facto time to observe the principles taught by Jesus nearly 2000 years ago in a troublesome Roman backwater. Christmastime is the season of Faith, Hope, and Charity.

Some Christians say they wish Christmas could last all year. Others say that Christmas’s pagan roots mean we shouldn’t celebrate it at all. I’m inclined to agree with the former. If we don’t know which day of the 365 is the real Christmas, best to hedge our bets, and make every day a holy day.