February 13

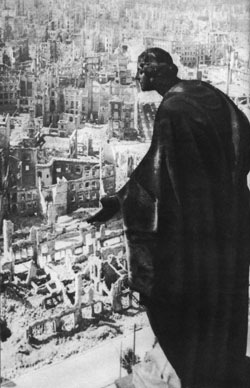

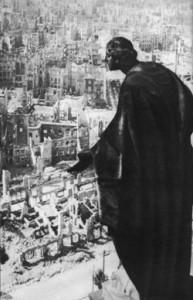

When I first visited Dresden in the mid-1990’s, to my eyes it looked like the city had just stepped out of World War II, even though, in retrospect, it must have undergone a great deal of renovation by that time.

Dresden miraculously survived the first five years of World War II intact, having dodged the Allied bombings that destroyed much of Berlin, Hamburg, and other German cities. Many Germans felt that the city had developed a de facto immunity, perhaps because of Dresden’s cultural significance, the beauty of its historic buildings, churches, and neighborhoods, and its diminished value as a military target.

For this reason, in early 1945 refugees streamed into the safe haven of Dresden from all directions. By February of that year, things were looking bleak for Germany; the Russians were closing in from the East, the British and Americans from the West. As stories of Russian atrocities filtered in from refugees from the East, Erika Dienel, a 20 year-old typist in Dresden, recalled the feeling on February 13:

“[W]ith a small ration of red wine, we brewed a hot punch and talked about where we would go should the Russians overrun us. But the Americans were also not too far away, and we only hoped they would come first.

The Americans did come first, but hardly in the way the residents of Dresden could have imagined.

When the air-raid sirens began that night at ten minutes to nine, Erika and her family headed down to the cellar.

25 minutes later, approximately 250 British and U.S. planes unleashed over 800 tons of explosives and incendiaries. The largest bombs weighed two tons and were called “block-busters” because of their capacity to take out a city block.

When Dresden residents came out of the basements to see their city in flames, they thought the worst was over. They were wrong.

Around 1:20 am, just as crews were trying to put out the flames, a second wave of over 500 bombers arrived, dropping 1,800 more tons of explosives on the city. Because the first bombs had destroyed the city’s air-raid siren system, most received no warning of the attack.

By the morning of February 14 the entire center of the city was engulfed in a firestorm. Waves of bombers continued. Just when survivors would think the bombings had ceased, they would begin again. The temperature in the center of the city reached 1600 degrees Fahrenheit. Thousands of families who sought shelter in their cellars suffocated to death as the oxygen was sucked up by the massive fires.

The bombings continued until February 15. Erika Dienel survived like many others by diving into the Elbe River:

“Dresden was to burn for seven nights and days…In the centre there was no escape. The town was a mass of flames. People, burning like torches, jumped into the Elbe on this cold February night…

Every house we passed stood in flames; under our feet there were bodies, nothing but bodies.”

Kurt Vonnegut was an American POW in Dresden during the attack. His experiences there inspired the novel Slaughterhouse V in which the main character, Billy Pilgrim, is part of a squad of prisoners whose job is to remove countless corpses from destroyed buildings and shelters.

The Dresden death toll will never be known because the city at the time housed hundreds of thousands of uncounted refugees. The lowest estimates are in the tens of thousands. The highest are around a quarter million

The following year Dresden residents held memorial ceremonies on February 13, but the Soviet-occupied territory was under strict supervision:

“Anything that makes 13 February appear as a day of mourning is to be avoided…It is the mayor’s opinion that if a false note is struck when 13 February is commemorated, this could very easily lead to expressions of anti-Allied opinion. This is to be avoided under all circumstances.”

Now however, Germans young and old gather in Dresden on the evening of February 13 and remember the lives lost here, known and unknown.

I was in Germany in March 2003, with a friend from East Germany, and learned Dresden was again a cultural landmark, “Paris of Germany” they called it, rebuilt like a Phoenix, except for the Dresden Church that remains as a reminder of the bombing.

That evening we turned on the TV see another city on fire. U.S. planes had just begun bombing the city of Baghdad.

My friend translated the reporter:

“Shock and awe.”