February 23

Today Russia celebrates Defenders of the Fatherland Day.

On February 23 (Julian Calendar) 1917, Russian women in Petrograd celebrated the 7th International Women’s Day. In response to food shortages caused by the war with Germany, the women of Russia’s capital city “poured onto the streets,” demanding “bread for our children” and “the return of our husbands from the trenches.”

(www.marxists.org/archive/kollonta/1920/womens-day.htm)

The protests gained momentum the following days when workers’ strikes forced the closure of hundreds of factories. On February 26 the Tsar, who was away conducting the war, ordered his general to disperse the demonstrators, now numbering in the hundreds of thousands, saying such disturbances were “impermissible at a time when the fatherland is carrying on a difficult war with Germany.”

(Tony Cliff Lenin: All Power to the Soviets)

Russian troops fired on the crowds, killing dozens of protesters. But the real problem for the Tsar was that many of the Tsar’s troops refused to fire on crowds and sided with the strikers. The clashes of February 24-27 claimed about 1500 lives on both sides. In the end the Tsar lost the support of his own troops, was forced to abdicate his throne.

But that’s not why the Russians celebrate on February 23.

Nope, it’s because of what happened on February 23 the following year.

Nicholas II’s abdication gave way to a Russian Provisional Government, led by Social Revolutionary Alexander Kerensky. Under Kerensky the government declared Russia a republic, pronounced freedom of speech, made steps to encourage democracy, and released thousands of political prisoners.

But Kerensky, perhaps because he was the former Defense Minister, continued to keep the Russians engaged in the disastrous war against Germany. Bad move. Like the Tsar before him, the war would be his downfall.

How Russia got its Soviet:

The Russian word soviet meant “council.” Soviets were workers’ councils with little power, set up in the wake of 1905’s Bloody Sunday.

The Bolsheviks were an extremist minority party and as such could not hold much sway in a democratic assembly. Instead Lenin and the Bolsheviks bypassed the Provisional Government entirely and consolidated their power in these urban workers’ councils known as soviets, the most prominent one being the soviet in Petrogad.

In 1917 their platform called for the seizure of land, property and industry by the peasantry and workers, for the transfer of power to the local workers’ councils, and for the immediate end of war with Germany.

In April few took the Bolsheviks seriously.

By November they ruled the country.

What happened in 7 months?

Under Kerensky’s Provisional Government food and supply shortages worsened. Mass numbers of Russian soldiers continued to defect. And the drain of resources for the war effort strangled the economy. Even though most people were against the war, political parties would not withdraw. Lenin and the Bolsheviks’ opposition to the war bought them enough support to pull off the armed uprising later called the “October Revolution,” which occurred in—you guessed it—November. (Gregorian)

After the uprising the Bolsheviks put forth a resolution before the Provisional Government to transfer political power to the soviets.When the Provisional Government voted it down (What a surprise) the Bolsheviks walked out. The next day the Bolsheviks, with the support of 5,000 members of the Russian Navy in Petrograd, issued a decree dissolving the Provisional Government.

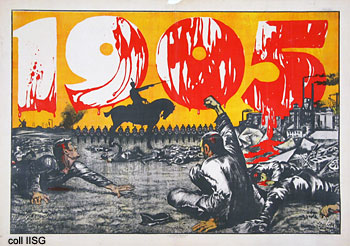

Lenin believed a standing army was a bourgeois institution and would not be necessary in a communist society; he was proved wrong. In order to ensure beneficial terms in an armistice with Germany, and facing a massive civil war, the Bolsheviks called for the establishment of a standing Workers’ and Peasants’ “Red” Army to replace the disintegrated Imperial Army.

The decree was issued on January 28. Ten days later on February 23* assemblies were held across the country to recruit soldiers for the new army. The “mass meetings brought 60,000 men into the Red Army in Petrograd, 20,000 in Moscow and thousands more in other places around the country.”

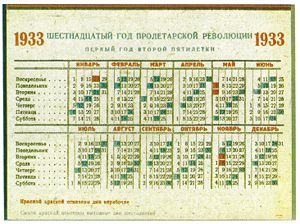

*(On February 1, 1918 Russia switched from the old Julian Calendar, abandoned by the West in the 16th through 18th centuries, to the Gregorian Calendar. As a result, the date February 1, 1918 in Russia was followed by February 14, 1918.)

February 23 was declared Red Army Day. It was changed to Soviet Army Day by Stalin. And to Defenders of the Fatherland Day following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Recently, according to dincarslan.blogspot.com…

“the long reaching poisonous arms of capitalism have found a new virgin field to exploit and made this day a “Men’s Day” where the women gives (or should give) gifts to their fathers, brothers, boyfriends and male colleagues.”

So, ironically, the date on which the Russians once celebrated women, February 23, is now a holiday extolling men.

Lyubov Tsarevskaya has a more traditional, patriotic view of the holiday:

“This is the ultimate reflection of one’s devotion and patriotism. As Jesus Christ said, Greater love hath no man than this, that a man lay down his life for his friends. (John 15:13) The history of the army in Imperial, Soviet, and now, Russian times is replete in stirring examples of self-sacrifice and heroism.”

The Chechens regard February 23 in a remarkably different manner:

On Army Day Chechens Quietly Remember Mass Deportation

It Has Been 63 Years Since the Deporation of the Chechens and Ingush