March 21

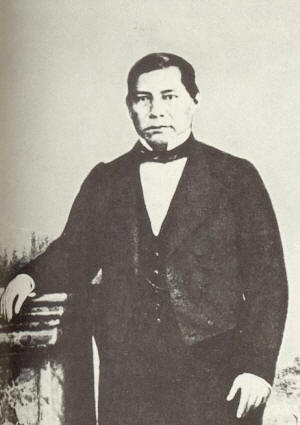

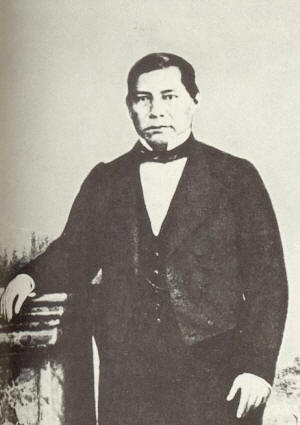

March 21, the birth of spring, is also the birth of Mexico’s greatest leader, Benito Juarez.

On this day in 1806 Benito was born to poor Amerindian peasants in the mountains of Oaxaca. His parents died when he was three and Benito spent his youth working the corn fields and shepherding local flocks.

At age 12 he left the mountain village for the city of Oaxaca to live with a sister and work as a servant. There he learned Spanish (he spoke only Zapotec, and was illiterate) and thanks to the help of a Franciscan monk he befriended, gained entrance to a seminary school. He chose to go to law school rather than become a priest.

He worked as a lawyer from 1834 to 1842, as a judge for the next five years, and by 1847 he was Governor of Oaxaxa. However, in 1853 he spoke up against the corrupt government of dictator Santa Anna, and was forced to go into exile in the United States. There the former lawyer, judge and governor worked at a cigar factory in New Orleans.

When General Santa Anna finally resigned in 1855, Juarez was welcomed back to Mexico. The new government sought to abolish the military government and create a new federalist constitution. Juarez, who had helped to draft a plan for a liberal Mexican democracy during his exile, was selected as the country’s Chief Justice under the new liberal President Comonfort.

The honeymoon was short. Conservatives angered by the country’s new democratic direction launched a coup with the support of the military and the clergy. The Mexican War of the Reform was a time of schismatic rule. At first Comonfort tried to negotiate with conservatives, led by General Zuloaga. He agreed to dissolve the Congress and place Juarez and other liberal leaders in jail. However, when it became clear the conservatives were not going to stop short of anything but complete militaristic control of the country, Comonfort reinstated Congress, freed Juarez and other political prisoners, and resigned. Juarez became, by default, the interim president of Mexico. Since Zuloaga’s forces controlled Mexico City, Juarez moved his government to the state of Guanajuato (meaning “place of frogs”).

Juarez’s legitimacy was aided by the power struggle between Zuloaga and two other generals, each of whom took turns arresting and deposing one another and assuming military control. When the dust cleared, liberal forces marched back into Mexico City and regained the capital. Juarez became undisputed President in 1861.

Faced with a bankrupt economy, Juarez declared a moratorium on European debts. Spain, England and France responded by seizing the port of Veracruz. Juarez struck an agreement with Spain and England to repay Mexico’s loans, but France had other plans. They intended to establish a puppet dictatorship under Maximilian I.

Again Juarez took his government into exile, this time to the state of Chihuahua. Juarez could not get support from the United States, which was in the middle of its own Civil War.

Juarez sought, and got, support from Mexican-Americans in California (recently Mexico) and after the U.S. Civil War, Lincoln and other generals unofficially supported the Juarez government with weapons and men.

Maximilian was overthrown and executed in 1867, at which time Juarez became undisputed president for his fifth and last term. He would die while in office at the age of 66.

“It is given to men, sometimes, to attack the rights of others, to seize their goods, to threaten the lives of those who defend their nation, to make the highest virtues seem crimes, and to give their own vices the luster of true virtue. But there is one thing that cannot be influenced either by falsification or betrayal, namely the tremendous verdict of history. It is she who will judge us.”

Benito Juarez to Emperor Maximilian