January 1

Today is the Granddaddy of all holidays. Celebrated around the world, New Year’s Day transcends culture, language and religion.

The strange thing is, how of all days did this arbitrary night–December 31 to January 1–come to represent the changing of the solar calendar? It is neither a solstice nor equinox, nor the anniversary of any momentous event.

- Russia once celebrated the New Year on September 1.

- The Chinese New Year falls in late January through early February.

- The French chose September 22, the autumnal equinox, during the French Revolution.

- Iran celebrated (celebrates?) on or around March 21, the spring equinox.

- The Hebrew calendar celebrates in early Fall.

- The Cambodian, Thai, and some Indian provinces in mid-April.

So what gives with January 1?

In fact the Roman calendar, on which ours in based, began with March. Which makes sense if you think about the names of the months:

- September: 7th month

- October: 8th month

- November: 9th month…

I was told in elementary school another reason why the months were off: it was because July and August, the months named after Julius Caesar and Augustus, were inserted after June.

Good theory. Wrong, but good theory.

The months of July and August were not “added” to the calendar but replaced the already existing months Quintilis and Sextilis. (Quintilis meant 5th and Sextilis 6th.)

So even in the time of Julius Caesar (45 BC) were 6 of the months of the year out of whack?

Yep.

The original Roman calendar, supposedly created by Romulus, the founder of Rome, began in March and ended in December. March signified the beginning of the planting year and December marked the end of harvest. The remaining 60 or so days, when crops were neither sowed nor reaped, weren’t counted as months, but an amorphous winter period. As Cecil Adams puts it:

“…3,000 years ago not a helluva lot happened between December and March. The Romans at the time were an agricultural people, and the main purpose of the calendar was to govern the cycle of planting and harvesting.” – How Come February Has Only 28 Days?

This amorphous period allowed farmers to based their months on lunar cycles, not on the solar calendar. Hence the unoriginal names:

- Quinctilis, 5th month, ie. 5th moon

- Sextilis, 6th month, ie. 6th moon

- September, 7th month, ie. 7th moon

- October, 8th month, ie. 8th moon…

Farmer Ted (or Theodocus in ancient Roman) knew he had to plant such and such during the first or second moon and harvest such and such during the 8th or 9th moon.

They didn’t number the dates of the month like we do (1-31), but counted forward or backward based on the different stages of the moon each month:

The Kalends: first day of the month, or new moon

The Ides: middle of the month, or full moon

The Nones: the quartermoons

As in:

Beware the Ides of March. (Shakespeare) ie. Beware the full moon of March, ie. March 15th.

or

Damn, I’ve got to renew my driver’s license by the fourth day before the Kalends of Quinctilis. (Nestor the Chronicler) ie. four days before new moon of July, ie. June 27th. (The Romans included the day they were counting from as day 1.)

If you’re not confused yet, wait. It just gets better.

So sometime around 713 BC Roman King Numa Pompilius decided to name and fix this no-man’s land between December and March. He named January after the god Janus, and February after the Latin word Februum, meaning purification. It was the end of the year and marked a time of atonement. (Maybe that’s why it’s the shortest month!)

Years at this time were not numbered, but were referred to by the names of the two consuls elected that year. So this year might be Bush-Pelosi, except consuls were elected yearly.

In the third century BC the date officials took office was fixed on the Ides of March (March 15).

A law in 153 BC arbitrarily moved that date up two and a half months to January 1st.

The Cambridge Ancient History states that this was done to hasten the appointment of Quintus Fulvius Nobilior, so he could quell uprisings in Northern Spain. (Liv. Per. XLVII, Cassiod. Chron.) [More on this here.] My theory is that, as stated earlier, Romans had nothing better to do in January and February.

The date stuck and January 1st marked the beginning of the Roman legal calendar, though it was not yet considered to be the start of the new year by the general Roman populace.

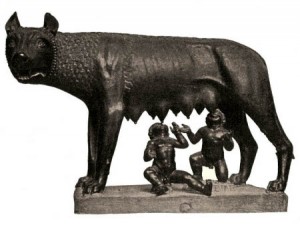

Below: Caesar celebrating New Year

[Oops, wrong picture]

By the time Julius Caesar came to town a couple of problems were apparent with the Roman consular calendar.

The most important being that it was 355 days, roughly twelve lunar cycles. That worked fine for a few years but after enough years March would fall in the dead of Winter and September would mark the beginning of Summer, leading to very confused farmers, not to mention cows.

The Roman Head Honchos (Honchos Headus Romanus) tried to fix this problem by periodically inserting an extra month called Intercalaris after February. (Think Leap Month.) However, with the lack of DSL and decent cell phone service among ancient Romans, it took a while for an Intercalaris to make its way to the average farmer in the countryside, causing citizens to be in different �months.

Also, the government could neglect to declare an Intercalaris for an extended time, as with the Punic Wars, leading to the “Years of Confusion” when the seasons went completely askew.

By the time Julius Caesar took power the calendar was off by approximately 100 days. He fixed this problem by extending the year 45 BC to 455 days. Then he changed the number of days in each month to create a 365-day solar calendar, rather than a lunar calendar. (Thank you Juli!)

Afterward, the calendar was also changed to refer to the year by the Emperor. So instead of being the year of Bush-Pelosi, for example, 2007 would be the 7th Year of the Reign of the Bush.

But wait there’s more!

Just when you thought it was safe to go back to the calendar, the Roman Church in the 6th century AD chose March 25, the date of the Annunciation, as the official start of its New Year.

The March 25th date also explains why December 25th, exactly nine months after the Annunciation, was chosen as the birth of Jesus.

However, the centuries-old Roman tradition of celebrating January 1 as the New Year could not be suppressed. January 1 was declared a Church holiday by Pope Boniface IX in 615 AD and called “Octave of the Lord.” The Pope’s mass was conducted at Rome’s Church of St. Mary. Hence the celebration became connected with the Virgin Mary and became known as “The Feast of St. Mary.”

The Gregorian calendar, proposed by Aloysius Lilius and approved by Pope Gregory in 1582, fixed the inaccuracies of the Julian calendar and set January as the 1st month yet again.

By this time many countries had already reverted back to the January 1st New Year:

- 1544 Holy Roman Empire

- 1556 Spain and Portugal

- 1559 Prussia, Denmark/Norway, and Sweden

- 1564 France

- 1576 Southern Netherlands

Other governments followed suit:

- 1583 Northern Netherlands

- 1600 Scotland

- 1700 Russia

- 1721 Tuscany

- 1752 Britain and colonies

It should be noted that the people of many of the above countries celebrated the Roman New Year’s Day on January 1st long before their governments recognized it. Britain for example considered March 25th as the beginning of the legal year, like a tax year, while the general populace celebrated on December 31st as the year’s end.

In essence, as late as the 1700’s the English-speaking world was continuing the 3,000 year-old Roman tradition–a year starting in March and ending in December.