February 3

Once a year in Japan, the land of order and politeness, it is considered perfectly acceptable behavior for children to hurl beans and peanuts at their classmates without reprimand.

That day is today, Setsubun, or Lunar New Year, and understandably, kids more than anyone carry on the tradition. Though Setsubun lacks the weight it commanded back in the 8th century, many Japanese do not let this day pass without tossing at least a few legumes inside and outside for good luck.

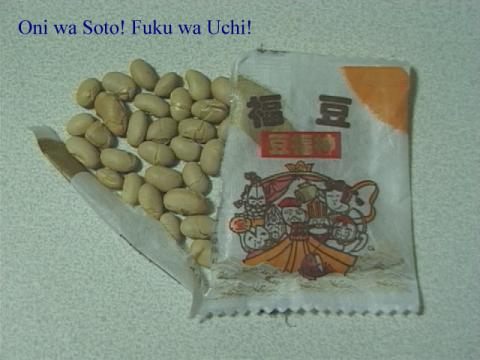

Mame Maki, the aforementioned bean-throwing activity, is meant to ward off evil spirits for the coming year. People scatter beans on the ground or toss them at imaginary Oni (roughly, demons or ogres) while yelling:

“Oni wa Soto, Fuku wa Uchi!”

(It looks and sounds worse than it is.) It’s pronounced Foo-koo, so watch your tongue, and it translates to:

“Get out, Demon/Ogre! Come in, Good Luck/Happiness!”

Mame Maki bears resemblance to the tradition at Western weddings of throwing rice grains to represent fertility.

Like American children on Halloween, Japanese schoolchildren wear Oni masks to represent the demons while their peers gleefully pelt them with beans and nuts, as an American schoolteacher in Japan describes here.

Traditionally soybeans have been the projectile of choice, but recently peanuts have been picking up steam. Both are sold in stores in small packets.

Another tradition is to eat the number of beans of your age today, plus one for the coming year.

This evening families eat a special thick sushi called futomaki, or hutomaki.

What you need to make: Ingredients

What you do to make: Directions

And they eat while facing a “lucky” direction–which differs each year.

Other ways to ward off the demon include piercing the head of a sardine with a holly branch and hanging it in a doorway.

Also, celebrities born under the current year’s zodiac sign (ie. 12 year-olds, 24, 36, 48…) can be seen on TV performing Mame Maki pubicly.

Setsubun means “division of the season.” There are four setsubun, throughout the year but the one celebrating the changing of winter into spring has always been the most auspicious. Similar to the Indian Makar Sankranti festivals and Celtic Imbolc, which both mark the coming of Spring.

Prior to 1873 Japan used a luni-solar calendar of 355 days. Every few years an inter-calaria month of 30 days was added to keep the lunar calendar in line with the solar.

After Japan adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1873, the spring festival began to wane, as Japan began celebrating New Year’s with the rest of the Gregorian world on January 1.

Setsubun used to be celebrated on the second full moon after the solstice. It now occurs every February 3.

Setsubun Protest 2010: Luck in! Peace in! Military bases out!

2 Replies to “Setsubun”