June 16

With the coming of summer, many students are struck with a debilitating illness known as cantgotoschoolitis. Symptoms may include inability to pay attention in class, wandering eyes, and an overactive imagination.

With students yearning so badly to get out of class, it’s hard to believe that on this day in 1976, many young students gave their lives fighting just to receive a fair and equal education.

In 1953, the white Apartheid government of South Africa passed the Bantu Education Act, which created a curriculum intended to reduce the aspirations and self-worth of the country’s black students.

As the Minister of Native Affairs and future Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd explained,

“When I have control of native education I will reform it so that Natives will be taught from childhood to realise that equality with Europeans is not for them…” (Apartheid South Africa, John Allen)

The supposed benefit of the Act was that it increased the number of black students able to attend school; the reality was that it provided no additional resources for the expansion. As a result, by 1975 the government was spending R644 per white student and R42 per black student.

The final straw came in the 1970s when the Apartheid government announced instruction would no longer take place in South Africa’s many native languages, but only in English and Afrikaans.

As one student editorial proclaimed:

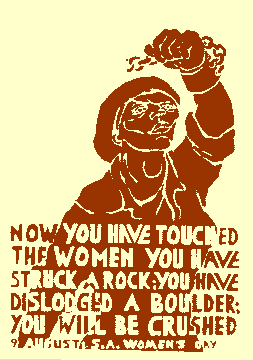

“Our parents are prepared to suffer under the white man’s rule. They have been living for years under these laws and they have become immune to them. But we strongly refuse to swallow an education that is designed to make us slaves in the country of our birth.” (South Africa in Contemporary Times)

The conflict came to a head on June 16, 1976 when a group of students held a protest against the educational system in Soweto. When students refused to disperse, police unleashed tear gas. Students responded by throwing rocks; police, by firing bullets. At least 27 students were killed in the massacre, including a 12 year-old boy named Hector Pieterson.

A string of protests and riots engulfed the region. June 1976 is considered one of the most divisive and tragic months in South African history.

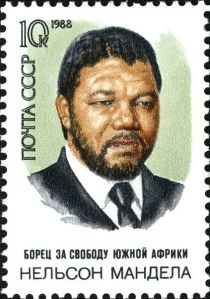

After the fall of the Apartheid government in the 1990s, South Africa chose to dedicate June 16 as Youth Day, in memory of those who died in the Soweto Riots, and those who devoted their lives to the long struggle for equal education and the abolition of apartheid.