January 14

Happy New Year!

It’s January 1 in the Orthodox Calendar, observed by Orthodox Churches in Russia, Macedonia, Serbia, and many of the former Soviet Republics, including Ukraine, Armenia, Belarus, and the one that’s all consonants. (Kryrrrgyztyrgystan)

So is Russia two weeks behind the times? Do they feel the need to have the last word on New Year’s Eve parties? Or does being torn between two New Year’s dates simply give them the chance to party for two full weeks?…(which the Russian winter could definitely use.)

Russian New Year

The story goes that up until the late tenth century, much of Russia and Byzantium celebrated the New Year during the spring equinox. That changed in 988 AD when Basil the “Bulgar-slayer” Porphyrogenitus* introduced the Byzantine Calendar to the Eastern Roman Empire.

The Byzantine Calendar was like the Julian Calendar except it began on September 1, and its “Year One” was 5509 BC—the year historians calculated as the creation of the world (Anno Mundi) according to genealogies of the Bible, from Adam to Jesus.

It took roughly four centuries for the “September 1st” New Year to make its way into the heart of Russia. And just when the Russians were getting used to that, Peter the Great switched to the Julian Calendar, moving New Year’s to January 1 in 1700 AD.

It was only a matter of 50 years until all of Protestant Europe stopped using the Julian Calendar altogether, in favor of the Catholic Europe’s Gregorian Calendar, leaving Russia and the Orthodox Church out in the cold.

So for the next two-hundred years, even though Russia celebrated New Year’s on January 1st according to their calendar, their entire calendar was about 11-13 days behind the rest of the West. (Which is why the Russian October Revolution took place in November.)

It wasn’t until 1918 that Lenin finally moved Russia to the Gregorian calendar.

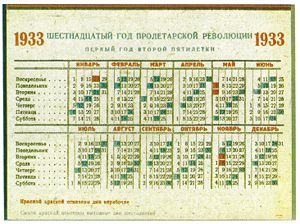

But the Soviet Union couldn’t let sleeping dogs lie. During the 1930s they declared war on the number 7, dividing months into five six-day weeks. Fortunately, this decade-long practical joke on the Russian people ended in June 1940.

These days, when it comes to the Old Calendar vs. the New Calendar, the Russians have tossed aside their austere ways and say, “Why choose? Have both!”

Most New Year celebrations happen on December 31st, but the holiday season continues until January 14. It’s a day of nostalgia, called Old New Year, a more sedate version of New New Year, often spent with family and watching the 1975 classic “Irony of Fate”, the Russian “It’s a Wonderful Life.”

Julian Day

Today we also celebrate day 2,454,846 in the Julian Day system—the number of days that have passed since noon, Greenwich Mean Time, January 1, 4713 BC. The Julian Day system was developed by Joseph Scalizer in 1582, and is used mainly by astronomers and people with way too much time on their hands.

*Basil’s title Porphyrogenitus means “born in the purple”. The title was bestowed at birth upon children who were (1) born to a reigning Emperor and Empress of the Byzantine Empire, and (2) born in the free-standing Porphyry (purple) Chamber in the Great Palace of Constantinople. (That’s why there’s less Porphygenituses than Smiths.)