July 14

As a child, I asked my father, “When was the French Revolution?”

He said, “It began in 1789.”

I asked, “When did it end?”

He said, “It’s still going on.”

* * *

Known as “Bastille Day” in English, Fete de la Federation (Holiday of the Federation) is one of the world’s most famous national holidays, but it’s more commonly known as le Quatorze Juillet (July 14).

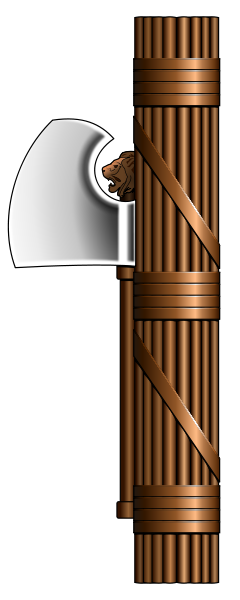

The Fete de la Federation commemorates the storming of the Bastille on July 14, 1789. Located in the heart of Paris, the fortress was built during the Hundred Years War as the Bastion de Saint-Antoine. After the war, kings used the Bastion to hold the “evildoers”, such as con-men, embezzlers, political prisoners and Protestants.

Over the centuries the large, imposing Bastille prison became the very symbol of the tyrannical monarchy.

- The Bastille

By 1789 France was in deep financial doodoo, in part from supporting the American War of Independence. King Louis XVI took the desperate step of calling together a body known as the Estates-General–a gathering of members of the clergy, nobles, and “everybody else”–to help solve the crisis. The Third Estate (the “everybody else” contingent) represented 97% of France’s population (Nobles and Clergy made up the other 3%) but could easily be outvoted by the other two Estates, as had happened the last time the Estates-General convened, in 1614.

“Since 1614, the economic power of the Third Estate had increased dramatically; in 1788, the popular call was to double the number of the representatives from the Third Estate so that they’d have equal voting power in comparison with the other two estates…TheParlement of Paris conceded the doubling question…but then declared that all voting would be done by individual Estates, that is, each Estate would get one vote.”

“Revolution & Tragedies in France”

Needless to say, this didn’t enthuse the Third Estate, which walked out of the meeting en masse and formed the National Assembly, joined by sympathetic clergymen and nobles. On June 19, 1789, the king locked and forbade entry to the meeting place of the newly-formed National Assembly, the Salle de Etats. Not easily dissuaded, the Assembly met on a nearby Tennis Court to take what became known as the Tennis Court Oath. Fearing that King Louis XVI would shut them out of the their new meeting place, members of the National Assembly vowed that they would not disband until they had created a Constitution for a new France, based on the principle that the government serve the people.

Tensions in Paris grew as King Louis filled the capital with Swiss and German soldiers, who were less sympathetic to the French populace than native-born soldiers. The final straw was not a shot or a massacre, but the king’s dismissal of his Finance Minister Jacques Necker. Necker had been instrumental in calling together the Estates-General, in doubling the membership of the Third Estate, and in involving the public in the financial affairs of the nation. The already discontented public saw his dismissal as an attack on their cause, and they feared King Louis XVI’s next step would be the dissolution of the National Assembly.

On July 12, thousands of Parisians marched onto the Palais Royal where a journalist and lawyer by the name of Camille Desmoulins jumped up on a table outside a cafe by the garden and was said to have yelled,

“Citizens, there is no time to lose; the dismissal of Necker is the knell of Saint Bartholomew for patriots! This very night all the Swiss and German battalions will leave the Champ de Mars to massacre us all; one resource is left; to take arms!”

In recent years, the debate about whether the besiegers of the Bastille sought to free political prisoners, or to take the weapons stored there, has favored the latter. There were only seven prisoners in the Bastille at the time of the siege. After a violent clash between the angry armed crowds outside the Bastille and the forces that guarded it, the crowds stormed the fortress, freed the prisoners, took the munitions, and reportedly decapitated the Bastille’s governor and placed his head on a spike.

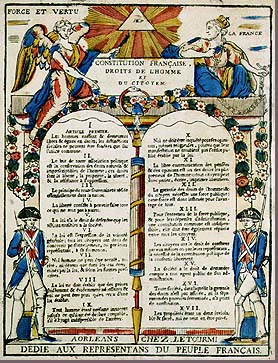

The 500 year-old symbol of French royal tyranny had come to an end; the following month the National Constituent Assembly gave birth to the Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. A document which declared equality not only for all French citizens, but for all men, for all time.

Exactly one year after the storming of the Bastille, Paris hosted the first Fete de la Federation in memory of the event. Hundreds of thousands or spectators gathered around the Champ de Mars to watch soldiers and national guardsmen of France’s 83 departments march, after which King Louis gave an oath to uphold the new Constitution. He would lose his head two and a half years later.