June 10

The feats of Arms, and famed heroic Host

from occidental Lusitanian strand,

who over the waters never by seaman crossed

fared beyond the Taprobane-land (Ceylon)

forceful in perils and in battle-post,

with more than promised force of mortal hand…Os Luíadas

June 10 is Portugal’s National Day, aptly known as “Portugal Day” or Dia de Portugal. Actually it’s longer, but few go around saying, “Happy Day of Portugal, Camões, and the Portuguese Community!”

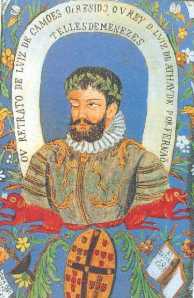

Portugal Day marks the death of writer, historian and adventurer Luís de Camões in 1580.

Camões wrote the Portuguese national epic Os Lusíadas , a history in verse of the Iberian nation and the era of discovery.

Compared to his writings, little is known of Camões’ real life. He was banished from Lisbon in 1546, supposedly because of an affair with a lady of the court. He served in the military for two years in Morocco, where he lost his right eye. He returned to Lisbon where the king (John III) pardoned him for injuring an officer in a street brawl; then spent 17 years in exile from his homeland, living in Goa, India and Macau, China. During these years he conceived of and wrote much of Os Lusíadas. Legend tells us he survived a shipwreck in the Mekong Delta in Vietnam, keeping his manuscript dry by swimming with one arm and holding it above the water with the other.

(The word “Lusiadas” stems from the tribe that occupied Portugal in ancient times, and refers to the Portuguese.)

Camões presented his masterpiece to King Sebastian in 1572 and won a small royal pension. However, he spent the end of his life in in a Lisbon poorhouse.

The year of Camões’ death, King Philip of Spain claimed the throne of Portugal after the disappearance of King Sebastian at the Battle of Alcácer Quibir. Portugal remained under Spanish control for sixty years.

Today, citizens of Portugal get the day off, the President addresses the nation, and Portuguese around the world gather to celebrate their homeland and their heritage.