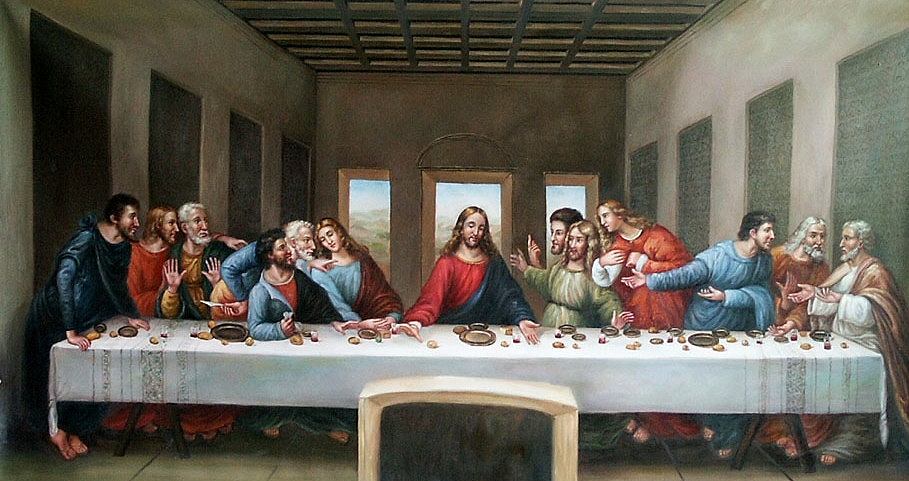

Holy Week comes to a close with the greatest and oldest of Christian holidays: Easter, or Pascha, celebrating the resurrection of Jesus.

The Easter we celebrate today encompasses a confluence of traditions and rituals that merged during the holiday’s transformation across 2000 years and even more miles from ancient Jerusalem, through Asia Minor, Greece, Rome, and Central and Western Europe.

The name Easter itself may be one of the many relics of ancient European paganism. Eostre, or Eastre, was a Germanic goddess. If the name bears a resemblance to the English word for the cardinal direction East, it’s no coincidence. East comes from same the Proto-Indo-European root as ‘dawn’. East is the direction where we see the rebirth of the sun each day, and Eostre was the goddess of the dawn.

The Venerable Bede wrote about Eostre back in the early 8th century, though by that time, he says, worship of the goddess had died out:

In olden time the English people…calculated their months according to the course of the moon. Hence after the manner of the Hebrews and the Greeks, [the months] take their name from the moon, for the moon is called mona and the month monath.

The first month, which the Latins call January, is Giuli; February is called Sol-monath; March Hreth-monath; April, Eostur-monath…

Eostur-monath has a name which is now translated Paschal month, and which was once called after a goddess of theirs named Eostre, in whose honour feasts were celebrated in that month. Now they designate that Paschal season by her name, calling the joys of the new rite by the time-honoured name of the old observance. — Bede, Caput XV: De mensibus Anglorum

There are divergent theories on Eostre. Many relate her to the pagan goddesses Astarte, Isis and Ishtar. Some historians however have cast doubts on the breadth of Bede’s claims about Eostre. and question her very existence.

The suspected pagan origin of the name in no way diminishes the reverence of the holiday for English-speaking Christians. Easter refers to the dawn and the direction of the rising sun, as well as to the ancient goddess, and as such it’s an applicable name for a holiday celebrating resurrection.

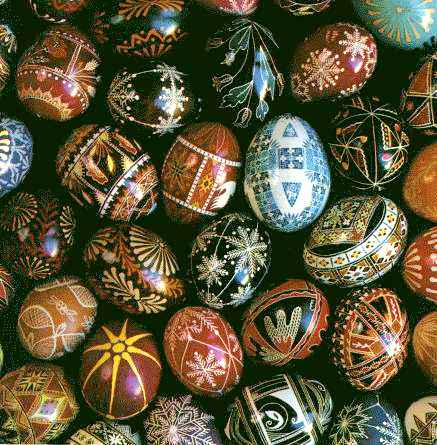

Other pagan pastoral traditions have become incorporated as secular, cultural rituals rather than religious ones. For instance, Easter eggs and the Easter bunny are ancient symbols of rebirth and fertility, common themes among Spring festivals.