March 24

“…as many people will die in Argentina as is necessary to restore order.”

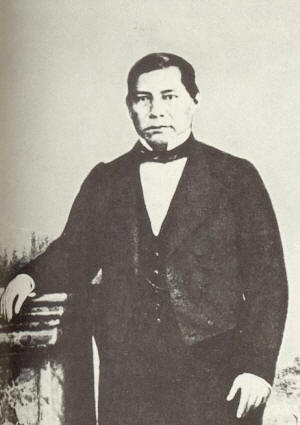

— Jorge Rafael Videla, October 1975

The film opens in the 1990’s with a teenage girl being called to the school office; there, Christina is essentially kidnapped by the government, taken away from her parents without even a phone call home, and forced to live with total strangers. Cautiva is a real-life horror story, where at first we believe we know who’s ‘good’ and who’s ‘bad’.

As the film progresses, we learn, along with Christina, a murkier, darker truth. The strangers are her real grandparents, and the people Christina believed were her parents, are not.

It turns out Christina was a child of the Disappeared, one of hundreds of babies taken from their true parents who were executed during one of the darkest chapters in Argentine history. Though Christina is a fictional character, her story is by no means unique.

In the 1970’s leftist guerrilla groups staged terrorist attacks on the conservative government in Argentina and foreign conglomerates. The violence caused President Isabel Martinez de Perón to appoint Jorge Rafael Vadila to head the army, and the government granted permission to law enforcement agencies and the military to “annihilate… subversive elements throughout the country.”

On March 24, 1976, Vadila and the army overthrew Perón in a military coup. The military junta—officially known as the “National Reorganization Process”—disbanded the legislature, revoked basic freedoms, and by 1977, had extended their targets far beyond mere combatants:

“First we will kill all the subversives; then we will kill their collaborators; then…their sympathizers, then…those who remain indifferent; and finally we kill the timid.”

— General Ibérico Saint Jean, governor of Buenos Aires, 1977

But they weren’t killed. They were ‘disappeared’.

Between 1976 and 1983, somewhere between 12,000 and 30,000 Argentineans “disappeared.” The true numbers will never be known. There were few official records. Thousands of ‘subversives’, activists, and those with the slightest association to them (or none at all) were taken from their homes in the middle of the night and never seen again. Many were brutally tortured in detention centers before being killed. But it was impossible for families of the victims to file murder charges since there were no bodies, no evidence of an arrest, no graves, nothing.

Through all this, the military junta still received support from the United States government, which was more concerned about protecting the Western Hemisphere from leftist elements.

Overestimating U.S. support, the military junta tried to increase popular approval by retaking the Falkland Islands from the British. But the U.S. supported Britain’s counterattack. The operation’s failure was partly to blame for the military junta’s loss of support from the people. Elections in 1983 returned a civilian government to power, which ended the disappearances, but granted immunity to the perpetrators, a pragmatic compromise to appease the still-powerful military. Relatives of the disappeared protested for years, demanding to know what happened to their loved ones and to see justice. The “Mothers of the Plaza del Mayo” met at 3:30 every Thursday for over two decades to protest the seven-year massacre and to honor their ‘disappeared’ children.

One crime the perpetrators didn’t receive immunity for was the kidnapping of children. During the ‘Dirty War’, hundreds of babies were taken from their ‘disappeared’ parents and given to families who supported the junta. It was for these kidnapping charges that many perpetrators were eventually convicted.

In the late 1980’s and 90’s the government chose to return many of the Children of the Disappeared, like Christina, to their biological grandparents.

In 2002 the Argentina National Congress declared March 24, the anniversary of the coup, as the Día Nacional de la Memoria por la Verdad y la Justicia—the Day of Memory for Truth and Justice.

atexaninargentina.blogspot.com/2008/03/day-of-memory-for-truth-and-justice.html