December 24

‘Twas the night before Christmas

And all through the store

Not a register was empty

Nor an inch of the floorFor the men of the nation

Had converged on this spot

To buy all the presents

They should’ve already bought.

Today my co-workers complimented me on my resistance to all the goodies lying around the office. It wasn’t resistance; it’s just that at this point my body weight is 90% chocolate, and the remaining ten is sugar.

My boss let us out early today (4:30) which gave me an hour and a half to do all my Christmas shopping.

Single women, if you want to find a man, go to any mall in America after 5pm on Christmas Eve. The stores are chock full of them. Take your pick. You will know one of these shoppers is a male because he has the same expression as a parachuter who has just been dropped in Uzbekistan with a map of Disneyland and a purse.

Believe it or not, there was a time when Christmas Eve was not associated with frantic mobs scavenging through Toys R Us for the last Diaper-Me Elmo, or whatever the current craze is.

That time was 1866. The following year, Macy’s department store remained open Christmas Eve until midnight for last minute shoppers, thus setting in motion the downward spiral that has consumed our society.

You’ll notice with a lot of Saints’ Days, that the “Eves” before are still more important than the Days themselves. The same goes for many Jewish, Muslim and Hindu holidays. In many calendars, the day once began at sunset, a time much easier for farmers to deduce than 11:59 pm.

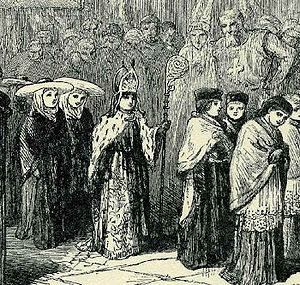

Some “Eves” were celebrated reverently with a mass at church. But many an Eve developed a reputation for merry-making. For example, Saint Nick’s Eve when townspeople would dress a boy up as a clergyman–a “Boy-Bishop” he was called–who would imitate a priest, much to the delight of onlookers. Sometimes mobs would sing bawdy songs while careening drunkenly through the streets in a haphazard procession, often harassing the social elite in the process.

This led to King Henry VIII’s infamous “party-pooper” decree:

Whereas heretofore divers and many superstitions and chyldysh observances have be used, and yet to this day are observed and and kept…as upon Saint Nicholas, Saint Catherine, Saint Clement, the Holy Innocents, and such like, children be strangelie decked and apparayled to counterfeit priests, bishoppes, and women, as so be ledde with songes and daunces from house to house, blessing the people and gatherying of money; and boyes do singe masse and preache in the pulpitt…

The Kynges Maiestie therefore, myndinge nothinge so moche as to advance the true glory of God without vaine superstition, wylleth and commandeth that from henceforth all such superstitious observations be left and clerely extinguished throwout his realmes and dominions, for asmuch as the same doth resemble rather the unlawfull superstition of gentilitie, than the pure and sincere religion of Christe.”

Of course, the King’s piety didn’t stop him from beheading his wives (or improve his spellyng). After the King’s death, his Roman-Catholic daughter Queen Mary rescinded the ban in 1554.

During Christmastime the ancient spirit of Saturnalia came out to play under the guise of Christianity, leading one 16th century Anglican bishop to pronounce, “Men dishonour Christ more in the twelve days of Christmas, than in all the twelve months besides.”

Oliver Cromwell banned the celebration of Christmas altogether between 1649 and 1660. And the Puritans in Massachusetts followed suit in 1659.

Rituals like those described above evolved into what we call “wassailing”. Members of the impoverished gentry would sing outside the residences of the social elite, asking, sometimes rather persuasively, for money, or at least booze—a cross between trick-or-treating and Christmas caroling, and the forerunner of both. (It was also a time for servants to impose upon their masters for tips, much like today’s Christmas bonuses.)

But according to Stephen Nissenbaum, author of The Battle for Christmas, it was a group of early 19th century aristocrats–disturbed by the uncouth December rituals of the gentry–who implemented many of the family-friendly traditions now associated with Christmas in North America. Jock Elliot in Inventing Christmas calls 1823 to 1848 the “Big Bang” of Christmas traditions. Chief among these: Saint Nicholas’s annual reindeer-powered sleigh jaunt on Christmas Eve, immortalized in Clement Clarke Moore’s “A Visit From Saint Nicholas” in 1822 and in Washington Irving’s short Christmas stories.

Nissembaum theorizes that Santa Claus served as a “Judgment Day” primer for children. Be good and get presents. Be bad and get coal. A more tangible way for parents to introduce their kids to Christian doctrine before jumping straight into Eternal Damnation. [The unintended flipside being that children, after learning “the truth” about Santa, may grow to apply the same lesson to the Judge Himself.]

Nearly 200 years later, through the miracle of modern technology we can track Santa’s journey in real time as he darts across six continents at 100 times the speed of a bullet train, according to the North American Air Defense Command, aka NORAD.

NORAD’s been tracking Santa’s Christmas Eve trips since 1955. According to legend, that was the year…

…a Sears store, at the time known as Sears Roebuck and Company, placed Christmas advertising that included a phone number where children could reach Santa Claus. The only problem was that the phone number was printed incorrectly.

Yes, the kids reached NORAD. Bombarded with calls, Air Defense personnel checked the radar and informed the children of Santa’s whereabouts.

As for me, I’m off to the land where the sugar-plums dance. So Merry Christmas to all and to all a good night!

Very, very interesting.