March 22

If you thought the American Civil War ended slavery in North America, you’re half right.

Cuba didn’t abolish slavery until 1869, and did so almost at the very moment of its independence from Spain.

Puerto Rico, also a colony of Spain, had to wait even longer.

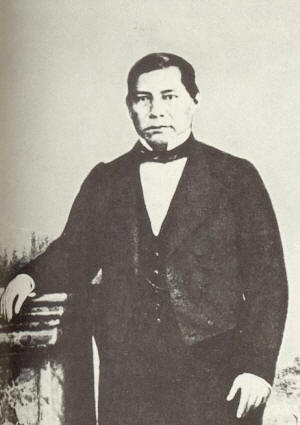

On September 24, 1868, about 500 Puerto Rican rebels had led an uprising against the Spanish government in the town of Lares. The Grito de Lares (Shout of Lares) was orchestrated by a doctor and surgeon named Ramón Emeterio Betances.

Betances was the son of a slave-owner, but became a symbol of the abolition movement in Puerto Rico. Also a proponent of good hygiene to prevent the spread of disease, he helped save the city of Mayaguez from a cholera epidemic in 1856. Still, his abolitionist activities caused him to be repeatedly exiled from Puerto Rico. After one exile in 1867, Betances traveled to New York where he founded the Revolutionary Committee of Puerto Rico. But it it was during his exile in St. Thomas that Betances drafted the Ten Commandments of Free Men:

- The abolition of slavery

- The right to vote on all impositions

- Freedom of religion

- Freedom of speech

- Freedom of the press

- Freedom of trade

- The right to assembly

- Right to bear arms

- Inviolability of the citizen

- The right to choose our own authorities

These are the Ten Commandments of Free Men.

If Spain feels capable of granting us, and gives us, those rights and liberties, they may then send us a General Captain, a governor… made of straw, that we will burn in effigy come Carnival time, as to remember all the Judases that they have sold us until now.

In 1868, Betances helped organized the first major pro-independence uprising in Puerto Rico. He asked Mariana Bracetti, the “Betsy Ross” of Puerto Rico, to knit the flag that rebels raised above the Lares church to declare Puerto Rico’s independence. The flag was red, white, and blue, similar to the Dominican Republic flag, which in turn was based on the French. (Betances had been inspired by the Declaration of the Rights of Man.) The rebels promised freedom to slaves who joined their cause.

The insurrection failed, but two years later (perhaps having learned their lesson from Puerto Rico) the Spanish National Assembly ordered the emancipation of all government-owned slaves, as well as all slaves over 60 and under 2, effectively freeing 10,000 slaves. On March 22, 1873, acting on a petition originally brought to Parliament in 1866, the Assembly voted to completely abolish slavery in Puerto Rico, liberating the remaining 30,000 slaves.

Jose Martí, a witness of the events of March 22, 1873, wrote:

The telegraph brought the yearned-for news to San Juan, whose population had had wind of it the day before, and hardly had the sun risen than all San Juan was in a state of fiesta…

…all of San Juan was flags, damask curtains, and blue hangings: one daring girl put a white rosette on one side of a blue drapery and a red one on the other….

Arm in arm, at the head of the procession, as if they were the freed slaves, went all those who with their voices and pens, actions and words, had fought to overthrow slavery: lawyers and doctors, youths and elders, merchants and writers.

Then the slaves went by, holding their children’s hands, the men in shirts and trousers, then women in white tunics and madras kerchiefs, some with their hats off, one of them leading a blind man, all of them silent…

…no one walked alone for all San Juan was a single family.

Despite the celebration, the slaves were still not free. The act of emancipation declared that they would remain slaves another three years. And their former masters were reimbursed in cash for the loss of their labor force.

Over 135 years later, Emancipation Day is celebrated each year on March 22 in Puerto Rico as one of the island’s most jubilant celebrations.

Puerto Rico Events and Festivities