April 11

If you grew up in El Norte, chances are your history books skipped the chapter on William Walker and Juan Santamaría. The two men could not have been more different.

Juan Santamaría was a poor laborer, an illegitimate son raised by a single mother in the impoverished district of Alajuela, Costa Rica. He joined his country’s army as a drummer boy in the 1850’s.

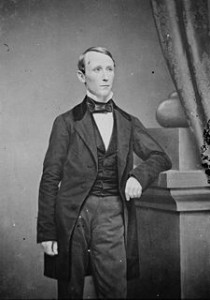

William Walker was born to a well-to-do family in the American South and graduated from college summa cum laude at age 14. He went on to study at some of the most prestigious universities in Europe before earning his doctorate in medicine at age 19. He briefly practiced law in New Orleans before moving to San Francisco where he explored the field of journalism.

Despite their different upbringings, the fates of these two men would become inextricably woven at Rivas, Nicaragua in April 1858.

While in San Francisco, Walker had conceived of a political opportunity south of the border—he gathered a group of pro-slavery supporters to help him establish slavery-friendly zones in Mexico and Central America.

For whatever reason, the government of Mexico had issues with Walker’s notion. When they didn’t capitulate, Walker raised an army and took Baja California by force. He proclaimed it part of a larger pro-slavery region that would be called the Republic of Sonora. Later defeats caused Walker to retreat. He was put on trial in the United States for inciting an unsanctioned war. And was acquitted by a jury in eight minutes.

The William Walker story doesn’t end there. It worked so well in Mexico, he figured why not spread the love to Central America.

Walker set his sites on Nicaragua. Before the Panama Canal, Lake Nicaragua was the gateway between the Atlantic and Pacific. The overland route could chop months of a trip around the Tierra del Fuego. Nicaragua had just undergone a serious period of destabilization—15 presidents in six years—making it ripe for exploitation.

With an invitation from one of the feuding Nicaraguan political parties, the Democrats, Walker and 57 men invaded Nicaragua. They captured the city of Granada. With the support of the Democrats, Walker set himself up as de facto ruler of the country.

At this time, the President of Costa Rica, Juan Rafael Mora, sensing Walker’s future ambitions, made a pre-emptive decision—to cross over into Nicaragua and attack, not on the country of Nicaragua itself but Walker and his forces.

The climactic battle between Walker and Mora was the Second Battle of Rivas. The inexperienced Walker made multiple military blunders prior to the battle, forcing the small army to hole up inside a thatched-roof hostel.

Enter Juan Santamaria. There couldn’t be a more compelling antidote to the overeducated and overprivileged Walker. At the time of the Battle of Rivas, the day laborer was a 25 year-old drummer boy in the Costa Rican army.

Though Walker’s forces were outmanned at Rivas, their position in the hostel gave them a distinct shooting advantage. Costa Rican General José María Canas called on a volunteer to approach the hostel and light the roof on fire with a torch. It was a suicide mission. Santamaría stepped forward, asking only that should he die, someone look after his mother.

Under heavy fire, Santamaría reached the hostel and threw the torch, igniting the roof. Santamaría was struck dead by enemy fire; however Walker’s men were forced to flee. Santamaría’s last act was the beginning of the end for Walker, and marked a symbolic turning point in the repulsion of foreign forces from Costa Rica and Nicaragua. Walker was executed by firing squad in 1860.

Sadly, the heroics of the Battle of Rivas were overshadowed by a devastating cholera epidemic that killed a tenth of the population of Costa Rica. But in the decades that followed, Santamaría’s legend emerged as the leading heroic figure symbolizing the unity of the Costa Rican people against imperialist forces. Because Costa Rica hadn’t fought for independence from Spain, the battle against William Walker became event that solidified the nationalist spirit.

Even today, the young drummer boy from Alajuela is the only Costa Rican to be honored with his own national holiday—April 11, the anniversary of his death and of the Battle of Rivas.

William Walker: King of the 19th Century Filibusters – historynet.com

Costa Rica in 1856: Defeating William Walker while creating a national identity

I will right away grab your rss feed as I can’t find your email subscription link or newsletter service. Do you have any? Please allow me recognize in order that I may subscribe. Thanks.