May 7

radio (adj.): (1) of, relating to, or operated by radiant energy; (2) of or relating to electric currents or phenomena (as electromagnetic radiation) of frequencies between about 3000 hertz and 300 gigahertz. — Webster’s Dictionary

I turn the switch and check the number

I leave it on when in bed I slumber

I hear the rhythms of the music

I buy the product and never use it

I hear the talking of the DJ

Can’t understand just what does he say?— Wall of Voodoo, “Mexican Radio“

In the 1940s and ’50s, the Soviet Union established May 7 as Radio, Television, and Communication Workers Day. Today the Russians know it as Radio Day, a commemoration of an event that occurred on May 7, 1895…

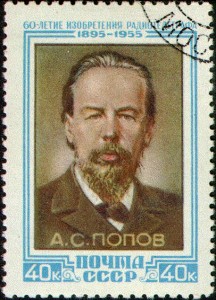

“It was on this date that [Alexander] Popov read a paper in the Physics Department of the Russian Physical and Chemical Society entitled, On the Relation of Metal Powders to Electric Oscillations.”

— “Alexander Popov: Inventor of Radio”, by M. Radovsky

Don’t you wish you could’ve been a fly on that wall?

Apparently, this was like being at opening night of Star Wars. Or maybe more akin to catching an Offspring concert back when they were playing coffee houses.

Either way, Popov’s demonstration of the practical application of electromagnetic signals at the Physics Department’s monthly meeting rocked the house, as evidenced by the official meeting minutes:

“A.S. Popov reported On the Relationship of Metal Powders to Electric Oscilliations… Utilizing the high sensitivity of metal powders to extremely weak electric oscillations, the speaker constructed an instrument designed to indicate rapid oscillations of atmospheric electricity.” — May 7, 1895

Say what you will, the Physics Department of the Russian Physical and Chemical Society knew how to party.

+ + +

In Russia, it is a well established fact that Popov invented the radio. That ‘fact’ is, shall we say, less established in the West, where inventors like Guglielmo Marconi and Nikola Tesla got the credit, and more importantly, the patents.

Ultimately, the creation and application of radio technology was made possible by the combined efforts of several scientists who each added vital pieces to the puzzle that would soon change the face of civilization. In 1898, Tesla showed off a radio-controlled boat in Madison Square Garden. In 1899, Marconi sent a wireless signal across the English Channel. Sir Oliver Lodge and Heinrich Hertz also made significant contributions. And in 1906 Reginald Fessenden conducted the first music/entertainment broadcast.

And, as they say, the rest was hysteria.

Just 16 years later, the New Republic predicted…

“There will be only one orchestra left on earth, giving nightly worldwide concerts; when all universities will be combined into one super-institution, conducting courses by radio for students in Zanzibar, Kamchatka and Oskaloose; when, instead of newspapers, trained orators will dictate the news of the world day and night, and the bedtime story will be told every evening from Paris to the sleepy children of a weary world; when every person will be instantly accessible day or night to all the bores he knows, and will know them all: when the last vestiges of privacy, solitude and contemplation will have vanished into limbo.”

— “The Ether Will Now Oblige” Bruce Bliven, The New Republic, Feb. 1922

Within a few decades of Popov’s first demonstration, parents were already complaining about kids’ brains rotting away from listening to too much radio.

A 1930’s New York Times article describes the general sentiment of an Atlantic City Teachers Association meeting…

“The task of teaching young radio listeners to discriminate and interpret is one of the new responsibilities thrust on the school room by radio’s increasing popularity among children, according to I. Keith Tyler…

“‘Boys and girls are now listening to the radio more than two hours a day,’ he said. ‘Their attitudes are being affected, their tastes altered and their understanding of life developed by this experience with the radio. We must develop their abilities to discriminate and interpret. Our loudspeakers pour out a withering barrage of political, economic, and social propoganda; a flood of verbose sales talk and great quatities of mediocre clap-trap.'” — New York Times, November 1938

So kids, the next time your parents complain about you wasting all your waking hours addicted to mindless drivel spewed by wireless devices, tell them their folks were doing it too! And bonus points for using the phrase “great qualities of mediocre clap-trap“.

As for the next wave of the future, a radio with moving pictures that premiered at the 1939 World’s Fair, the Times didn’t have high hopes for it:

“The problem with television is that people must sit and keep their eyes glued to the screen; the average American family hasn’t time for it. Therefore the showmen are convinced that for this reason, if no other, television will never be a serious competitor of broadcasting.” — New York Times editorial, 1939 [Futuring: the Exploration of the Future]

Etymology:

The scientific breakthrough was originally known as “wireless telegraphy” and “wireless telephony”. Then “radio-telegraphy” and “radio-telephony”, referring to radiating energy (see definition above) like the prefix in radioactivity, and by 1906 the Telegraph Age reported:

“…the British post office…has adopted the word ‘radio’ as the designation for a wireless telegram.” — Telegraph Age, April 1906 (earlyradiohistory.us)

love the N.Y. Times editorial!

I thought the New Republic article was uncanny, way ahead of its time…

The description sounds more like the Internet than radio.