July 6

It’s a busy week in the Czech Republic, where inhabitants celebrate not one, but two public holidays in honor of not two, but three prominent theologians. Yesterday Czechs and Slovaks alike honored the Saints Cyril and Methodius, and today Czechs recall national hero Jan Hus, the forerunner of Protestant Reformation who was burnt at the stake on this day in 1415.

The late 14th century was not the best of times for the Papacy. Having just returned from 70 years in France, later called the “Babylonian captivity” of the Papacy, French cardinals were eager to elect another French Pope. Riotous Roman crowds had another idea. Under duress the cardinals elected a Neapolitan to the Papacy in 1378, then hightailed it back to France to elect the “real” French Pope. Of course both Popes retained the title, and governments around Europe were forced to declare allegiance to one or the other.

Jan Hus grew up in Bohemia during this tumultuous epoch. He studied at the recently-established University of Prague, becoming a professor of theology in 1398, a priest at Bethlehem Chapel two years later, and eventually rector of the University.

Hus was an outspoken proponent of church reform. At this time the Church owned nearly half the land in Bohemia, yet taxed the poor rampantly. Hus spoke out against abuses in the church, including the widespread indulgence system which undermined the sanctity of Christian piety. He supported the preaching and reading of the Bible in common languages, and he opposed the recent doctrine of Papal infallibilit. Most controversially, Hus made the ‘heretical’ claim that the final authority of Christian Law lay not with pope, but with the Bible.

In 1409, in an attempt to end the papal Schism, bishops at the Council of Pisa elected a third Pope (Alexander “the Antipope” V) to replace the other two. However, rather than resolve the Schism, this only resulted in three concurrent Popes.

Jan Hus and his supporter King Wenceslaus declared allegiance to the third Pope, but when Alexander V’s successor issued a new wave of indulgences to raise money for a war against the King of Naples, Hus proclaimed that no pope or bishop had the right to take up the sword in the name of the Church. In rallying his followers against the indulgences, he also lost the support of King Wenceslaus who was sharing in the profits.

In 1414 Hus was asked to journey to Council of Constance (which sought to end the Schism once and for all), to which he was assured safe conduct by the Emperor of Luxembourg. When he arrived he found himself put on trial by the Council and imprisoned in Gottlieben Castle in chains. The bishops had convinced the Emperor that promises of safe conduct did not apply to heretics.

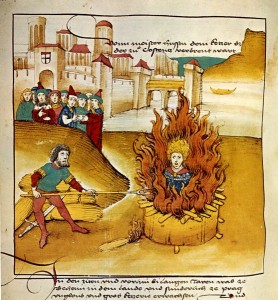

Hus was given many chances to recant his writings. He deplored false interpretations of his works, but stated he could not renounce beliefs unless they could be proven untrue by the words of the Holy Scripture. He was condemned to death in July 1415. Just before his execution he declared,

God is my witness that I have never taught that of which I have been accused by false witnesses. In the truth of the Gospel which I have written, taught, and preached I will die to-day with gladness.

Hus was also said to have uttered a prediction that in 100 years a man would come whose calls for reform could not be ignored, foreshadowing Martin Luther and the Protestant Revolution.

Hussitism and the Heritage of Jan Hus