September 8

Happy Birthday Madonna!

No, not that one.

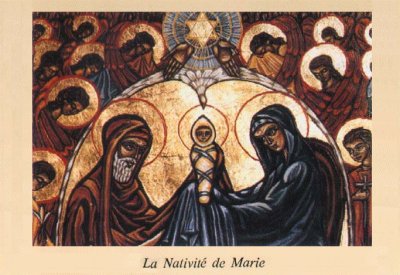

On September 8, the Catholic world celebrates the birth of the Virgin Mary.

Little is know of Mary’s birth from the Bible. The Gospel of James (which didn’t make the final cut) list her folks as Joachim and Anne (Hannah). The couple was childless until they were visited by an angel who informed them a child was forthcoming. Anne promised the child would be brought up to serve the Lord.

Mary would have been born “Mariam” or מרים

For two-thousand years, the Virgin Mary has been the symbol of feminine spirituality in Christian culture. While Eve was unfairly vilified as the bringer of original sin throughout the Middle Ages, Mary represented the opposite, the ultimate purity and the the bringer of God.

Pope John Paul ll in his 2000 millennium message elevates the status of both Eve and Mary. He describes Eve as the original symbol of Humanity, the mother who gave birth to Cain and Abel, and Mary, who gave birth to Jesus, as a symbol of the New Humanity; one in which All Humanity is One in Spirit with God. This statement changes the context which the Christian doctrine has relegated to women; that the Spirit of God resides equally in male and female.

Contemplation of Mary – St. Mary’s at Penn

Visions of the Virgin Mary have been spotted by worshippers throughout the Christian world. One of the most famous of these was witnessed initially by three children in Fatima, Portugal in 1917.

On the Nativity of the Virgin Mary, many Mediterranean and Latin-American villages carry her statue from local churches through the streets. Local Spanish processions are known as Virgin de la Pena, Virgin de la Fuesanta, and Virgin de la Cinta. Peru has the Virgin of Cocharcas, and in Bolivia it’s the Virgin of Guadalupe.

And it may not be Madonna (Madonna Louise “Like A Virgin” Ciccone)’s birthday, but singer-songwriter Aimee Mann turns 51 today…and rumor has it she’s still a Virginian.

Easter comes and goes

Maybe Jesus knows…