April 1

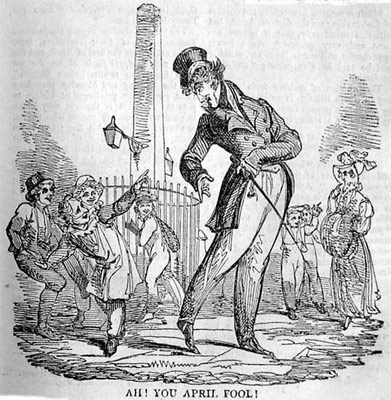

In the west, the first day of this month starts with a funny thing called the First April Fools day. The day might be a day of befooling others with fun and jokes, however, here in the east it brings endless tales of happiness but mostly sad stories, accidents and tragedies out of this nonsensical fools day on first of this month.

The first of April some do say,

Is set apart for All Fools Day

But why the people call it so,

Nor I nor they themselves do know.— Poor Robin’s Almanack, 1760

April Fools Day is one of those grand traditions, handed down from generation to generation, where one generation along the line forgot to tell the next precisely WHY we observe it. Which begs the question:

Who’s more foolish, the fool or the fool who follows?

— “Old Ben” Kenobi, 1977

No one really knows from where the bizarre April ritual originated. For centuries the English and Scottish on April 1 sent fools on “sleeveless errands”—fruitless or futile tasks. “That like ‘bootless’ cries?” No, the English have no grudge against uncovered limbs. Bootless comes from the same root as ‘booty’—the treasure, not the footware (or the 3am call). A bootless offense was an unforgivable one, for which no amount of monetary payment, or booty, could bring absolution or pardon. A sleeveless errand on the other hand, probably comes from sleave, meaning a thread or something tangled. The classic sleeveless errands were sending fools on the hunt for the “History of Eve’s Mother” or for “pigeon’s milk.”

“My landlady had a falling out with him about a fortnight ago for sending every one of her children upon some sleeveless errand, as she terms it. Her eldest son went to buy a halfpenny worth of incle at a shoemaker’s; the eldest daughter was despatched half a mile to see a monster; and, in short, the whole family of innocent children made April fools.”

In Scotland the phrase of the day was “Hunting the Gowk.” Gowk meant cuckoo. The leading Gowk trick in Scotland was to

“get some unsuspecting rustic to take a note to another man who is in the scheme. The envelope is sealed, of course, and inside is the sentence:

“This is the First of Aprile; Hunt the gowk another mile.”

The man to whom the note is addressed says he is not the right person to receive it, and sends the bearer on another mile by the directions inclosed.”

The French have been April fooling since at least the 16th century when New Year’s was changed from late March to January. The story goes that people would make fun of those throwbacks who still celebrated in spring, the Old New Year’s. Such fools living in the past were called “April fish.”

19th century writers suggested that April Fool’s Day roughly corresponded with the Hebrew month during which Noah sent the dove on the fruitless mission to find land after the Genesis flood.

But many also noted that April 1 was about the same time as the Indian festival of “Huli” (Holi), during which time similar customs, or at least good old-fashioned merry-making took place. During Holi Hindu social roles are forgotten, and neighbors blast each other with brightly colored powders.

The Persians meanwhile celebrated (and still do) Sizdah Bedar 13 days after the spring equinox. But that’s a story for tomorrow…

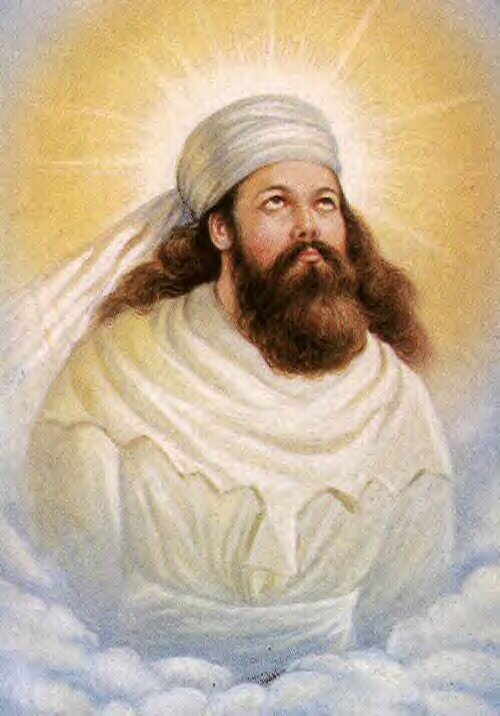

“Zoroastrianism is the oldest of the revealed world-religions, and it has probably had more influence on mankind, directly and indirectly, than any other single faith.”

“Zoroastrianism is the oldest of the revealed world-religions, and it has probably had more influence on mankind, directly and indirectly, than any other single faith.”