December 30

Polyglot:

1. A person having a speaking, reading, or writing knowledge of several languages.

2. A book, especially a Bible, containing several versions of the the same text in different languages.

3. A mixture or confusion of languages.

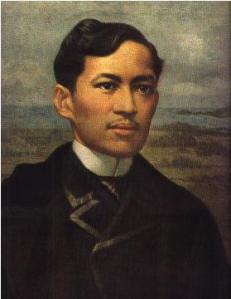

Today the people of the Philippines mourn the death and celebrate the life of their national hero Jose Rizal.

“I die without seeing the sun rise on my country. You who are to see the dawn, welcome it, and do not forget those who fell during the night.”

This eerily self-fulfilling prophecy was spoken not by Rizal, but by Elias, a character in Rizal’s great novel Noli Me Tangere, written almost a full decade before Rizal’s own execution.

Rizal wrote Noli Me Tangere (literally, “Touch Me Not”) at age 25. By that time Rizal had earned his Bachelor’s degree (at 16) in the Philippines; he had studied medicine at the University of Santo Thomas, but after witnessing discrimination against Filipino students, he sailed to Spain to complete his studies at the University of Madrid; he specialized in ophthalmology, due to his mother’s worsening blindness; and he earned a second doctorate at the University of Heidelberg.

“I spend half of the day in the study of German,” Rizal wrote, “and the other half, in the diseases of the eye. Twice a week, I go to the bierbrauerie, or beerhall, to speak German with my student friends.”

Rizal spoke at least a dozen languages–some sources say 22–including, Spanish, French, Latin, Greek, German, Portuguese, Italian, English, Dutch, Japanese. He translated works from Arabic, Swedish, Russian, Chinese, Greek, Hebrew, and Sanskrit into his native tongue of Tagalog. While in Germany, he was a member of the Anthropological Society of Berlin, for which he delivered a presentation in German on the structure and use of Tagalog.

But it was his novel Noli Me Tangere that would earn him fame in the Philippines and infamy in Spain.

Noli Me Tangere exposed the hypocrisy of the Spanish clergy in the Philippines and the injustices committed against native Filipinos. And his follow-up non-fiction work demonstrated that contrary to 300 years of colonialist teachings the Filipino people had been an accomplished nation before the Spanish set foot in the country. That in fact, colonization had resulted in a ‘retrogression’.

In response to Noli Me Tangere, clergy members circulated pamplets warning Catholics that reading the novel was equivalent to “committing mortal sin.”

The book was banned in many parts, and one anonymous “Friar” wrote to Rizal, “How ungrateful you are…If you, or for that matter all your men, think you have a grievance, then challenge us and we shall pick up the gauntlet, for we are not cowards like you, which is not to say that a hidden hand will not put an end to your life.”

Rather than give in to harassment, Rizal followed it up with a sequel, El Filibusterismo. Rizal’s novels became a rallying point for nationalists in the Philippines. In Spain he continued to fight for equal rights and representation for his countrymen. Rizal returned to the Philippines in 1892. After a rebellion broke out, Rizal was arrested and sent into 4 years of exile.

While in exile in Dapitan he managed a hospital, provided services to the poor, taught language classes, and worked with soldiers to improve the area’s irrigation and agriculture.

In 1896 the Philippines Revolution broke out. Though Rizal emphasized non-violence in his works, he was again imprisoned, and this time sentenced to execution.

Just before his death, Rizal wrote his final poem, which he ‘smuggled’ out to his sister by hiding it in the stove in his cell. The poem has no title, but is often called “Mi ultimo adios”…My last good-bye.

“My idolized country, sorrow of my sorrows,

Beloved Filipinas, hear my last good-bye.

There I leave you all, my parents, my loves.

I’ll go where there are no slaves, hangmen nor oppressors,

Where faith doesn’t kill, where the one who reigns is God.”–from Mi ultimo adios

He was executed by firing squad at 7:03 am on December 30, 1896, and buried without a coffin.

His tragic death only strengthened Filipino resolve for self-determination.

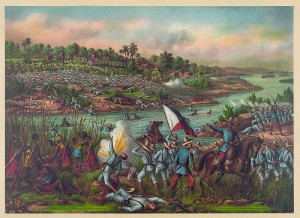

In April 1898, the fight for independence, led by Andres Bonifacio and Emilio Aguinaldo, received a boost from an unexpected party: the United States. The Spanish-American War, which had begun in Cuba, soon stretched to all of Spain’s remaining Pacific territories.

That summer the Philippines Army, headed by Aguinaldo, defeated Spanish troops, and handed over 15,000 Spanish prisoners to U.S. forces, along with valuable intelligence. Aguinaldo declared the Philippines an independent nation on June 12, 1898.

The Philippines soon found they had rid themselves of a demon only to make a deal with the devil. In defeat Spain ‘ceded’ the Philippines to the U.S., which immediately rejected Philippine independence. Whereas the Spanish had sought to bring Catholicism to the Philippines, the U.S. sought to bring “freedom” and “civilization”. The war that followed, the U.S.’s first overseas experiment in nation-building, took the lives of over a quarter million Filipinos (a low estimate), the overwhelming majority of them civilians. Disease and famine were a prime cause of civilian deaths. But torture, mass executions, internment camps, village-buring, and other atrocities against civilians were also staples of the war.

The war officially ended in 1902, but fighting continued until 1913. English, spoken by a minority of Filipinos, was declared the official language.

The Philippines would not see independence until after World War II, fifty years after the death of Jose Rizal. Through that time and even to the present, Rizal and his writings continue to symbolize the Filipino spirit and their long fight for equality and self-determination.

Our Mother Tongue

The Tagalog language’s akin to Latin,

To English, Spanish, angelical tongue;

For God who knows how to look after us

This language He bestowed us upon.As others, our language is the same

With alphabet and letters of its own,

It was lost because a storm did destroy

On the lake the bangka in years bygone.Jose Rizal, age 8 (originally in Tagalog)

This information about the Phillipines was new to me–and very interesting.

I never thought that the story that leads to the independence of Philippines is so dramatic.

The Philippine-American War is one of those overlooked chapters in U.S. history, and until recently was referred to as the Philippines “Insurrection” in American history books, a term Filipinos were, understandably, not very happy about.

Thank you for telling me about a period of history of which I knew nothing.