February 16

“The Council of Lithuania in its session of February 16, 1918 decided unanimously to address the governments of Russia, Germany, and other states with the following declaration:

“The Council of Lithuania, as the sole representative of the Lithuanian nation, based on the recognized right to national self-determination, and on the Vilnius Conference’s resolution of September 18-23, 1917, proclaims the restoration of the independent state of Lithuania, founded on democratic principles, with Vilnius as its capital, and declares the termination of all state ties which formerly bound this State to other nations.

“The Council of Lithuania also declares that the foundation of the Lithuanian State and its relations with other countries will be finally determined by the Constituent Assembly, to be convoked as soon as possible, elected democratically by all its inhabitants.”

These short paragraphs are what the nation of Lithuania celebrates today, February 16, as its independence day. A declaration that declared an end to over a century of Russian occupation.

Lithuania was first united in the thirteenth century by the enigmatic Mindaugas. (No, he was not a Harry Potter character, that’s Mundungus.) Mindaugas was the first and last King of Lithuania. He converted to Christianity to attain the support of the Pope and the Livonian Order, but reverted back to Paganism after. He and his wife Morta were crowned King and Queen in 1253. When she died ten years later Mindaugas made the fatal mistake of taking Morta’s sister as his wife. She was already married to a former ally of Mindaugas, Daumantas. Mindaugas was used to annexing numerous lands, but Daumantas did not take the annexation of his wife so readily, and helped Mindaugas’s nephew assassinate the King along with two of the king’s sons. Never again was there crowned a king of Lithuania.

By the end of the 1300s Lithuania was the largest state in Europe. Its land included parts of what is now Belarus, Ukraine, Poland and Russia.

One gift the Lithuanians bestowed upon Eastern Europe during the 16th century was the codification of its laws in the Three Statutes of Lithuania. The Sobornoye Ulozheniye, the first complete code of Russian law, was based in part on the Lithuanian codes.

A political bond with Poland endured in various manifestations through the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries until the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was eaten up piece by piece by the superpowers growing around it: Prussia, Austria, and mainly Russia.

Catherine II of Russia’s attitude was: “Polotsk and Lithuania have been taken and retaken about twenty times, and treaty was ever concluded without one side or the other claiming part or all of it, depending on circumstances.“

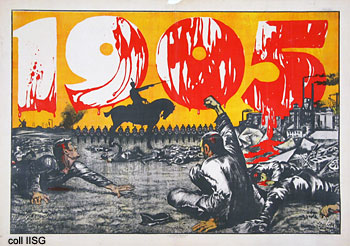

Lithuania remained under Russian control for over a century. During World War I the Lithuanian government exploited the weakness of the Russian Empire and the animosity between Russia and Germany. A Council of Lithuania passed a series of Acts starting in late 1917 and early 1918 which repudiated Russian rule. Germany, which occupied parts of Western Russia, was happy to see pieces of the Russian Empire break away, thinking they would pick up the crumbs. However, when Germany began losing the war in 1918 their position to negotiate declined. And with the Act of Independence of February 16, 1918, Lithuania achieved independence from both Russia and Germany.

The celebration was short lived. During World War II Lithuania was overrun by Soviet tanks on their way to Poland, followed by German tanks on their way to Russia, and again by the Soviets on their way to Berlin.

January 13, 1991, the Soviet Union, fearful of increasing nationalist sentiment in Lithuania invaded the city of Vilnius and attacked the TV tower and other buildings. Images of the attack spread throughout the world, and were influential in the eventual fall of the Soviet Union eight months later.

The short Act of Independence of 1918, with its emphasis on democratic principles, was cited by Lithuanians as the inspiration for and the basis of the rebirth of their sovereign state.

Blogs of note:

http://irzikevicius.wordpress.com

EU Newcomer Lithuania celebrates 90 years of Independence