April 7

He stood the aged palms beneath,

that shadowed o’er his humble door,

Listening, with half-suspended breath,

To the wild sounds of fear and death,

Toussaint L’Ouverture!— Toussaint L’Ouverture, by John Greeleaf Whittier

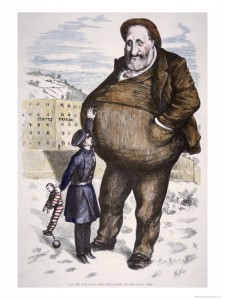

Toussaint L’Ouverture was born a slave in French Saint Domingue, now Haiti, in 1743. Many legends are told of his early life. He was nicknamed “Walking Stick” due to his narrow stature, and was later described as more charismatic than attractive.

At the age of 33 he was given his freedom. He married and by all accounts he had settled into a quiet life by 1791. By that time word of the French Revolution and its ideals of Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity had reached Saint Domingue, and the slaves and free men of color hoped the promises of the “Declaration of the Rights of Man” would extend to them. When it became apparent no such action was forthcoming, the slaves revolted in the Boukman Rebellion of of 1791. Slavery was banned in 1793.

During the 1790’s the three great European powers, France, Britain, and Spain, were all vying for control of the colony. Toussaint joined the army, first working as a doctor; within a few years, now in his early 50’s, he underwent an unbelievable professional trajectory. Toussaint went from being an ordinary Haitian living in peace to an unparalleled military genius and the governor of Saint Domingue. A former black slave who would defeat the armies of the greatest European empires.

Toussaint became governor of Saint Domingue in 1797. Professing allegiance to France, he chased the last Spanish forces off Santo Domingo in 1801.

Toussaint next sought to make Saint Domingue an independent, permanently slave-free nation. Napoleon, seeking to reintroduce slavery to the island, sent 20,000 troops to the island to retake and depose of Toussaint.

“At the head of all is the most active and indefatigable man one can imagine. One can definitely say that he is everwhere and above all in the place where sound judgement and danger lead him to believe that his presence is the most essential. His great sobriety and the ability given only to him of never resting, the advantage he has of going back to office work after a tiresome journey, of replying to a hundred letters a day and of habitually exhausting five secretaries.”

— Colonel Vincent, in a note to Bonaparte. The Gilded African, Wendy Parkinson

Though initially told he could return to civilian life, Toussaint was betrayed and kidnapped by French forces, and was taken to a remote fort in the high French Alps. Unused to the freezing temperatures and kept under the harshest conditions, Toussaint died in French captivity on this day (April 7) 1803.

The U.S.’s second President (1796-1800), John Adams, voice of the American Revolution two decades earlier, had supported the L’Ouverture revolution against European colonialism.

Adam’s successor Thomas Jefferson felt otherwise:

“I become daily more & more convinced that all the West India Islands will remain in the hands of the people of color; & a total expulsion of the whites sooner or later take place. It is high time we should foresee the bloody scenes which our children certainly and possibly ourselves (south of the Potomac) have to wade through to try to avert them.” — Letter to James Monroe, July 1793

When Haiti gained won its freedom in 1804 under the command of one of Toussaint’s generals, Jefferson, a strong ally of the French, refused to acknowledge Haiti’s independence. The island nation would have to wait until 1862 when Abraham Lincoln’s administration finally recognized it. Ironically, the Jefferson administration owed a great deal to L’Ouverture. It was L’Ouverture’s defection and uprising in Haiti that forced Napoleon to sell their continental North American possessions—the Louisiana Territory—to Jefferson for a song.

Toussaint, the most unhappy man of men…

O Miserable Chieftan! Where and when

Wilt thou find Patience? Yet die not; do thou

Wear rather in thy bonds a cheerful brow:

…There’s not a breathing of the common wind

That will forget thee; thou hast great allies;

Thy friends are exultation, agonies

And love, and man’s unconquerable mind.— William Wordsworth

“His political performance was such that, in a wider sphere, Napoleon appears to have imitated him.”

— Citizen Toussaint, Ralph Korngold